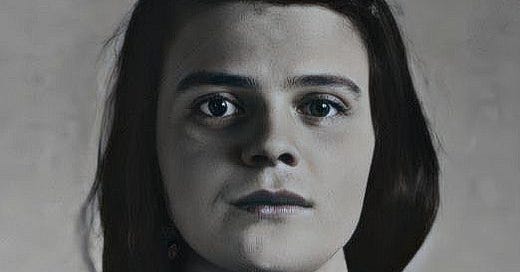

At first glance, Sophie Magdalena Scholl was an unlikely candidate to play a major role in a key resistance movement in Nazi Germany—and for that matter, in history.

Sophie was born in 1921 to an upper middle-class family in the south of Germany, the fourth of six children. When she was ten years old, her family moved to Ulm, where her father served as a state auditor and tax consultant.

When the Nazis rose to power in 1933, Sophie and most of her siblings eagerly became part of the Nazi party’s youth movement. Sophie joined the Bund Deutscher Madel, the Band of German Maidens, and rose quickly in its ranks. Her brother Hans was part of the Hitler Youth, the sole official boys’ wing (and sometimes paramilitary group) of the Nazi youth movement.

Sophie’s family was rooted in the tradition of Christianity. Her parents fostered a home environment that valued critical thinking, passionate debate, and honest, open conversation. Critics of the Nazi party, the elder Scholls viewed its developments with horror, and were deeply aghast at their children’s enthusiastic participation in its activities.

Sophie and her siblings also participated in non-Nazi-affiliated associations that encouraged a love for nature and the outdoors, as well as the music, art, philosophy, literature, and aesthetics of German romanticism, the dominant intellectual movement of its time. These organizations, originally seen as compatible with Nazi ideology, were dissolved over time—and by 1936, banned. Hans Scholl remained active in one of these associations. In 1937, he and several of his siblings were arrested for their participation. For Sophie, their arrest inaugurated a process of reflection that would eventually end her support of the Nazi system.

In September of 1939, Hitler invaded Poland from the West. They partnered with the Soviets, who violated a non-aggression pact to invade Poland from the East. Days later, France and England declared war on Germany, and the older Scholl brothers were sent to fight on the front lines.

After graduating from high school in 1940, Sophie began a mandatory six-month term in the auxiliary war service as a nursery school teacher. The military-adjacent nature of the service caused Sophie to further question her understanding of Nazi ideology. She began to engage in passive forms of resistance. She explored the writings of the Christian theologian St. Augustine of Hippo, a champion of human freedom. (St. Augustine also espoused some oppressive views as well, but I digress.)

In May of 1942, Sophie entered the University of Munich, where she began to study biology and philosophy. Her brother Hans, already studying medicine there, included her in his circle of friends. Sophie began to keep a diary: She recorded the evolution of her views, and expressed her desire for autonomy, an end to the War, and happiness with her boyfriend, Fritz Hartnagel. Sophie’s doubts about the Nazi regime continued to grow. (I’ve reflected a great deal on how much courage and curiosity it must have taken to question an authoritarian regime like Nazism, and to do so in a context in which open questioning would result in imprisonment.

In the meantime, Sophie’s brother Hans and his friends, while serving on the frontline of the war, had seen firsthand the atrocities committed in Poland and Russia. They grew more critical of the Nazi system, and refused to remain quiet.

In June of 1942, shortly after Sophie began her studies, Hans and his friends began to print and distribute leaflets in Munich to call their fellow students and citizens to action against the Nazi regime. By fall of that year, they had written and distributed four pamphlets. Sophie saw the pamphlets and lauded their contents; when she learned that Hans belonged to the group, she demanded to join it.

Called the Weiße Rose, or White Rose, the group was a modest endeavor. In time, it would have far-reaching impact. At its center were Sophie, Hans, and their fellow students at the University of Munich: Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, and Kurt Huber, a professor of philosophy and musicology.

Together, the members of the Weiße Rose published and distributed six pamphlets, first using just a typewriter and the a mimeograph machine, which enabled them to make copies.

Paper and stamps were scarce during wartime; the group asked everyone they could trust, including Sophie’s boyfriend Fritz, for supplies. They distributed the pamphlets carefully by mail, sending them in small quantities so as not to arouse suspicion. Sorting through telephone books for addresses and handwriting each envelope, they sent the materials to professors, booksellers, authors, and friends. They amassed a network of supporters that stretched as far north as Hamburg and as far south as Vienna, allowing them to reach thousands of households across Germany.

As 1943 dawned, the group felt empowered and full of hope. Their efforts were beginning to take hold, alarming the authorities and igniting debate among their peers. They began to make connections with other resistance groups. The voices of dissent at the University of Munich grew louder.

The group members became bolder, beginning to distribute the flyers in person and peppering walls around the city of Munich with slogans like “Down with Hitler” and “Freedom.”

The group’s second leaflet denounced the persecution and mass murder of the Jews.

The group’s sixth—and as it would happen, its last—bore the words:

“Even the most dull-witted German has had his eyes opened by the terrible bloodbath, which, in the name of the freedom and honour of the German nation, they have unleashed upon Europe, and unleash anew each day. The German name will remain forever tarnished unless finally the German youth stands up, pursues both revenge and atonement, smites our tormentors, and founds a new intellectual Europe. Students! The German people look to us! The responsibility is ours: just as the power of the spirit broke the Napoleonic terror in 1813, so too will it break the terror of the National Socialists in 1943.”

On the cold Munich morning of February 18th, 1943, Sophie and Hans were distributing flyers at the university for fellow classmates to find as they walked between classes.

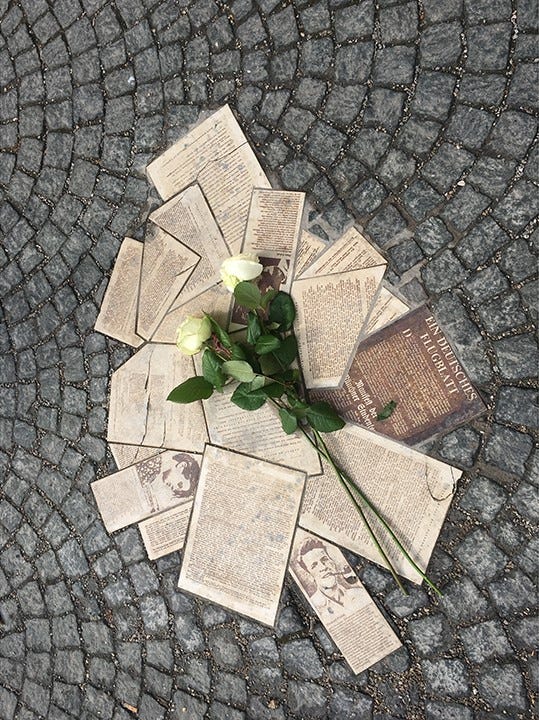

In a moment of bold impulse, Sophie pushed a stack of flyers off a balcony railing into the university’s central hall. The papers cascaded into the air like a murmuration of birds, crisscrossing one another before plummeting to the ground.

The flight of the papers was spotted by a janitor who happened to be a staunch supporter of the Nazi regime. He called the Gestapo, who immediately arrested Sophie and Hans. The draft for the seventh pamphlet was discovered tucked away in Hans’s bag.

The main Gestapo interrogator was Robert Mohr, who at first thought Sophie innocent. But Hans confessed—also, some say, naming fellow member Christoph Probst. Immediately thereafter, Sophie assumed full responsibility in a bid to protect the other members of the White Rose. (Imagine the sheer bravery, the selflessness, this must have taken!)

Four days later, on February 22, 1943, Sophie, Hans, and Christoph were tried for treason.

At 4:00 p.m., they were judged guilty and condemned to death.

Prison officials were so impressed by the bravery of the three that they allowed them to smoke cigarettes together before their executions.

At 5:00 p.m. that day, the guillotiner beheaded Sophie Scholl, then only 21 years old.

They executed Hans Scholl at 5:02 p.m., and Christoph Probst at 5:05 p.m.

Sophie’s last known words remain a matter of dispute. But it just so happened that during the four days between her arrest and execution, Sophie shared a cell Else Gebel, a communist member of the German resistance to Nazism.

They spoke often during those four days, offering one another support and solidarity. Else remembers Sophie’s last words to be these:

“How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause... It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go. But how many have to die on the battlefield in these days, how many young, promising lives? What does my death matter if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted? Among the student body there will certainly be a revolt.”

After World War II ended, Gebel retained many memories of her cellmate, which were presented in film in Fünf letzte Tage (1982) and Sophie Scholl – The Final Days (2005). Else Gebel died in 1964.

In total, the White Rose authored six pamphlets denouncing the Nazi regime’s atrocities and oppression, and calling for resistance. Before the deaths of its three most central members and the imprisonment of the rest, they had spread a remarkable 15,000 copies throughout Germany.

The 3rd leaflet bears words that seem even more significant today:

“Why do you allow these men who are in power to rob you step by step, openly and in secret, of one domain of your rights after another, until one day nothing, nothing at all will be left but a mechanised state system presided over by criminals and drunks? Is your spirit already so crushed by abuse that you forget it is your right—or rather, your moral duty—to eliminate this system?”

But the story doesn’t end there.

After Sophie’s death, German jurist Helmuth James Graf von Moltke smuggled a copy of the sixth pamphlet out of Germany to England.

Just three months after Sophie’s execution, in April of 1943, the New York Times wrote about student opposition in Munich. And that June, in England, Thomas Mann spoke of the White Rose’s actions in a BBC broadcast aimed at German citizens.

In mid-1943, the royal Air Force dropped millions of copies of the treatise, now titled The Manifesto of the Students of Munich, over Germany.

_____________________________________________

In post-war Germany, the White Rose was revered, and is so even today.

Countless schools, streets, and a prestigious award are named after individual members, the group itself, or Sophie or Hans Scholl.

Sophie’s bravery reminds us not to remain silent in the face of atrocities.

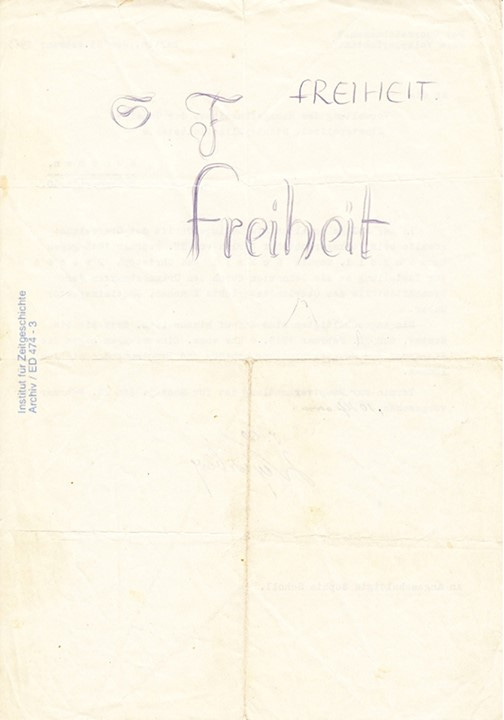

Her willingness to risk everything for the humanity of others reminds us to continue to fight for what Sophie wrote on the back of her indictment, just one day before her execution:

“Freedom.”

Fritz Hartnagel, Sophie’s boyfriend, was evacuated from Stalingrad in January of 1943, but could not return to Germany in time for Sophie’s execution.

In October of 1945, Fritz married Sophie’s sister Elisabeth.

_____________________________________________

I have reflected often lately on Sophie’s process. On her integrity, and the ultimate sacrifice she made so that Nazism could be defeated.

This puts me in mind also of heroes like Malcolm X, who also spoke out against his own group, the Nation of Islam.

And Ofer Cassif, a member of the Israeli Knesset who has been outspoken about his pro-Palestinian stance. In the late 1980’s, Cassif did jail time for refusing to serve in Israel’s military force in the Occupied Territories (of Palestine).

Cassif ignited a political and social media firestorm last week when he signed the petition supporting South Africa’s charges of genocide against Israel. (The petition is currently under review with the International Court of Justice is in the Hague.)

Cassif wrote on X, the platform previously known as Twitter,

“My constitutional duty is to Israeli society and all its residents. Not to a government whose members and its coalition are calling for ethnic cleansing and even actual genocide. They are the ones who harm the country and the people, they are the ones who led to South Africa’s appeal to The Hague, not me and my friends.”

And 18-year-old Tal Mitnick is currently serving a thirty-day jail sentence in Israel—one that will be renewed indefinitely—for refusing to serve in the Israeli Defense Forces.

According to a piece in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, Mitnick and a group of peers drafted a letter in September stating that they would not serve in the Israeli military despite the universal requirement of conscription. They wrote,

"We, teenagers who are about to draft, say no to dictatorship—both in Israel and in the occupied Palestinian territories–-and announce that we will not serve until democracy is guaranteed to all, to everyone who lives under Israeli rule."

Before his arrest, he affirmed his belief that “slaughter does not solve slaughter, and violence does not solve violence.”

There are so many others who throughout history have spoken out from within a powerful group to bring attention to that group’s injustices.

Without them, many of us would not be alive today.

I think about the ways in which dissent and fear of dissent live side by side in our bodies.

Anyone paying attention to Israel’s ongoing ethnic cleansing and genocide of Palestinians can see that the governments and media outlets of the U.S, the U.K., Canada, and much of Europe have actively suppressed and punished dissent for their own political ends, and to avoid punishment. They have actively refused to portray equal coverage of the war.

And anyone paying attention can witness the frequency with which prominent people, and even ourselves, have lost followers, colleagues, and business opportunities.

The talent agency that represents the artist and activist Amanda Seales decided to stop representing her.

Spyglass, the studio that produces the Scream franchise, fired actor Melissa Barrera for her pro-Palestinian social media posts. The same happened to Susan Sarandon.

And it’s happening across the United States and the U.K.

These are the kinds of crackdowns on political dissent that we decry in other, usually non-Western, countries, like in Russia, Hungary, or China.

Now more than ever, powerful voices of dissent like Sophie Scholl, Malcolm X, Ofer Cassif, Tal Mitnick, Amanda Seales, Melissa Barrera, and even your own dissenting voice, are necessary.

This year isn’t just an election year in the United States. As Time Magazine states, it’s the election year worldwide. More voters than ever before will head to the polls as 64 countries prepare to hold national elections. These countries, the magazine estimates, represent approximately 49% of the world’s population.

Prosocial dissent, the kind that benefits humanity, is more critical to our survival as a species than ever.

Nothing less than our humanity is at stake.

If you’ve missed my other pieces on the conflict, check out the following:

Should We All Just “Stick to Yoga?” (a piece on yoga + social justice)

A “Talking Points” guide to the Israel-Palestine Conflict

An article about the children of Gaza

A stunning interview on the Israel-Palestine conflict with Gabor Mate and his daughter

A piece on Israel’s indiscriminate destruction of Palestine’s olive trees

A column on the making of refugees

Dissent is our First Amendment right. We also have the right to peacefully protest the actions our government takes in our name. Such reprisals for espousing currently "unpopular" opinions is not only unConstitutional it's morally and ethically wrong.

How do we as a nation ever evolve into one that actually puts into practice the high ideals put forth in our founding documents if we refuse to learn from our past mistakes, refuse to learn about the effects of our current actions?

Thank you for this awesome letter. The movie Sophie Scholl - The Final Days is well worth watching. It actually was suggested in a course I took, Understanding World Religions under the Christianity section. Also, there is a book, historical fiction, The White Rose Network by Elie Midwood which I thought was well written.