What The Olive Trees Know

This weekend, I woke in the middle of the night, my thoughts filled with the olive trees of Palestine. A weight lay on my chest, so heavy that I struggled to take a full breath.

The world’s attention has been focused on Palestine since shortly after the terrible events of October 7th and the answering retribution on the part of Israel. My thoughts have also rested on the olive trees, who have themselves been immersed in a cycle of unspeakable violence and ecocide.

Olive harvest season in the West Bank spans the months of October and November. Most years, family and friends unite to pick the fruit from groves passed down through generations of ancestral inheritance.

The olive tree holds deep significance: It forms the root system of Palestinian economy, culture, history, identity, and religion.

Olives are a main source of income for more than 80,000 Palestinian families. According to United Nations’ figures, olive trees make up approximately 48% of the agricultural land in the West Bank and Gaza. They account for 70% of fruit production in Palestine, and comprise 14% of the Palestinian economy.

Olive oil production makes up almost all of the olive harvest; the rest is made into soap, table olives, and pickles. The olive production itself is reserved for local use; surplus is often shared with community, and a small portion exported to Jordan. With the rising global interest in organic food and fair-trade practices, Palestinian olives now also factor in European and North American markets.

Yet olive trees carry more than just an economic significance in the lives of Palestinians.

A tree can take as many as twelve years to bear fruit; each lives an average of 2,000 years. Tending to these trees is a multi-generational task that spans millennia. That olive trees live and bear fruit for thousands of years testifies to Palestinians’ history and continuity with and on the land.

Olive trees are slow-growing and long-living. Draught-resistant and with the capacity to thrive amid poor soil conditions, they are the embodiment of Palestinian resilience and resistance.

The World’s Largest Olive Tree

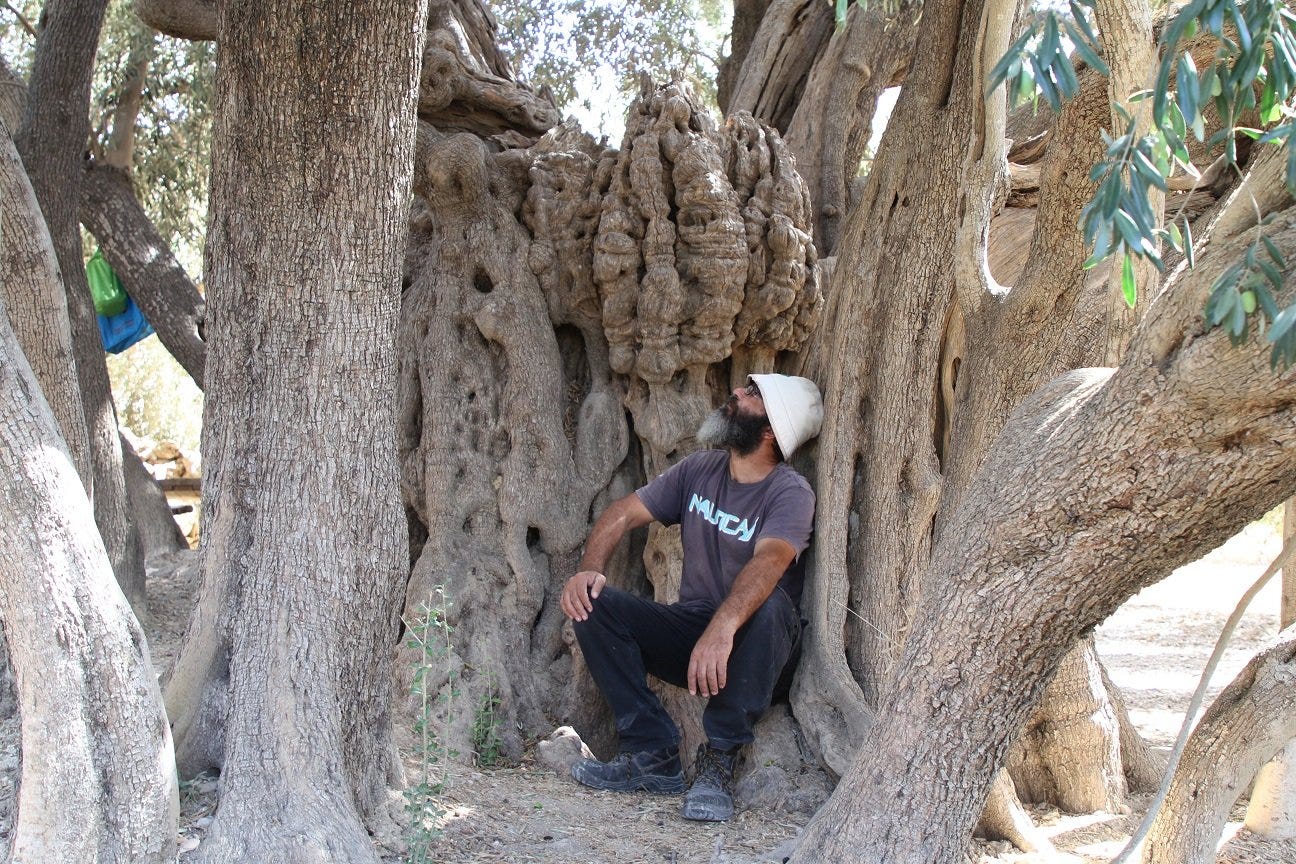

Travel to is found in Al Walaja, a small town within the municipality of Bethlehem, and you will find Al Badawi, arguably the oldest olive tree in the world. The tree, a source of pride for Palestinians, is estimated to be around 5,000 years old. It stands at 13 meters in height and extends over 250 square meters; its roots extend roughly 25 meters below the surface.

The tree has been given numerous names over the centuries: “Mother of Olives,” “Palestine’s Bride,” and “The Old Woman.” Palestinian Salah Abu Ali, the tree’s caretaker, says that Al Badawi is “no less important than the al-Aqsa or Ibrahimi mosques.”

The Olive Tree as the Centerpiece of Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

As this year’s harvest begins, groves of olive trees on the occupied West Bank continue to be targets of growing violence by Israeli settlers and the Israeli Defense Forces.

Such attacks typically increase during harvest season, which spans the months of October and November. During one incident of property demolition by the Israeli army in June of 2019, the United Nations documented the razing of nearly 400 Palestinian-owned trees in the same area.

Since the Six-Day War that took place from June 5-10 of 1967, Israeli settlers and military personnel have uprooted or cut down over one million olive and fruit trees in occupied Palestine. Dr. Cesar Chelala, an Argentinian-born physician and writer living in the U.S., contends that violence against olive trees are also attacks on Palestinian culture and survival.

Called arboricide, the destruction of trees is also a grave crime under international humanitarian law. It violates Article 54 of the 1977 Protocol to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, which prohibits the "starvation of civilians as a method of warfare". The article states:

"It is prohibited to attack, destroy, remove or render useless objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, such as foodstuffs, agricultural areas for the production of foodstuffs, crops, livestock, drinking water installations and supplies and irrigation works, for the specific purpose of denying them for their sustenance value to the civilian population or to the adverse Party, whatever the motive, whether in order to starve out civilians, to cause them to move away, or for any other motive."

To replace the uprooted olive trees, the Israelis brought in European pine trees, which were chosen to “make the landscape look less alien, more European” and “to obliterate all physical traces” of Palestinian heritage.

However, the Palestinian indigenous farmers have always considered pine trees as counterproductive for their environment as they “consume large amounts of water” and cause droughts. Water is scarce in Palestine, and pine trees do not fit into a seamless ecosystem between land and people.

In the religious scriptures of the bible, Qur’an, and Torah alike, the olive tree holds symbolic value. Attacks against olive trees therefore also violate Jewish teachings.

According to Sonja Karkar, founder of Women for Palestine in Melbourne, Australia, uprooting olive trees is contrary to the Halakha (collective body of Jewish religious law) principle whose origin is found in the Torah.

“Even if you are at war with a city,” the principle states, “you must not destroy its trees.”

The politicization of the olive tree is evident at every knot and gnarl of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, including the most recent election in Israel.

Israel’s War on Palestine’s Olive Trees

The politicization of the olive tree is evident at every twist and turn of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, including the recent election in Israel.

Days after Benjamin Netanyahu’s campaign promise in September of 2019 to formally annex the Jordan Valley, the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA) issued an order to uproot hundreds of olive trees owned by Palestinians in the valley right before a planned harvest.

As Israeli settlements continue to expand in the West Bank, clashes between settlers and Palestinians have surged, often manifesting in the targeting of farmers and their properties—particularly during the harvest season. Israeli authorities and settlers have uprooted over 800,000 Palestinian olive trees since 1967, according to research from the Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem.

Two E.U. heads-of-mission reports conducted in 2012 found that violent Israeli settler attacks against Palestinians targeted farmers in particular. Israeli NGO Yesh Din found that out of 211 reported incidents of trees cut down, set ablaze, stolen, or otherwise vandalized in the West Bank between 2005 and 2012, only four resulted in police arrests.

For nearly 15 years, hundreds of volunteers worldwide travel to the West Bank each year to accompany Palestinian farmers to olive groves in high-risk areas. A group of local Palestinians formed the organization To Be There in 2013. It is one of many locally and internationally who recruit volunteers for the harvest.

“Their impact is multidimensional,” says Baha Hilo, one of To Be There’s founders. “It’s about understanding, bearing witness, and buying time so that families can harvest as much as they can.” Members of the organization have observed that Israeli settlers and soldiers behave differently when internationals are present; this increases Palestinians’ sense of safety and their feeling that their plight is not ignored—that they are not invisible.

In 2006, nine human rights organizations filed a petition urging the Israeli high court to allow Palestinian farmers safe access to their olive groves during the harvest. The petition was unanimously granted.

Many Jewish activists now assist the planting of new olive trees to replace some of those uprooted by the Israeli settlers. On several occasions, the organization Rabbis for Human Rights has donated saplings to Palestinian communities affected by the uprootings.

Arboricide: A Mechanism of Colonial Violence

Burning, uprooting, and damage of trees has long been a mechanism of colonial violence.

The invading British cut down the sacred trees of Australia as one of their first acts of violence. Trees of great significance to Aboriginal communities continue to be destroyed.

In Victoria, the Djab Wurrung people are trying to stop the government from cutting down its native trees. These include the xanthorrhoea or grass tree, the damun or Port Jackson fig tree, and the sacred waratah or silky oak tree, an icon of Australia and the symbol of New South Wales. The government has also felled eucalyptus trees, including birthing trees where countless generations of their people have been born. This is a cultural and environmental loss for all Australians.

The Mapuche people of the Southern Andes live in the great and ancient Araucaria forests, which have been similarly devastated by governments that allowed extensive logging. The Mapuche revere the trees as sacred and refer to them as family members. They rely on the piñon (pine seed) of the tree as a staple in their diet.

This has also happened throughout the United States, Canada, and other locations of colonial settler violence.

Jakelin Troy, professor and Director of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research at the University of Sydney, says this about trees:

In Indigenous philosophies, all elements of the natural world are animated. Every rock, mountain, river, plant and animal all are sentient, having individual personalities and a life force. Trees are also one-stop-shops for all our needs, and sustain us with their generosity. The hard bark creates our houses, soft paperbark wraps our babies, stringy bark twists into fishing lines and cords, water carriers are carved from knots, leaves and fruits are our food and medicine, and roots and branches become tools that make our lives easy. Trees provide us with inspiration for our art and give us the aesthetic of the landscape. When the invading British, as one of their first acts on our Country, cut them down, we wept and cried with the trees, sharing their pain and shielding them with our bodies. When we destroy trees, we destroy ourselves. We cannot survive in a treeless world.

My body understands this loss on a cellular level.

Before World War II broke out in 1939, my mother lived on her family farm in Eastern Poland in what was then known as Reduta, Poland. To begin the war, Germany invaded from the West. The Soviets invaded from the West; they came to my family’s farm, gave her parents thirty minutes to get their three children dressed, and placed them on cattle cars bound for Siberia. The cars were open, with slats in the top for ventilation. Many people froze to death; the trains stopped once per day to cast the bodies of the dead into the snowy tundra around them.

The invaders seized capital and devastated the ecosystem, including farmland and animals. German node of assault alone destroyed a full 75 million square miles of trees equal to 400,000 hectares of forest, was cut down. The loss in agriculture and cultivation was devastating: 1,908,000 horses, 3,905,000 cattle, 4,988,000 pigs, and 755,000 sheep. The losses due to the Soviet part of the invasion were never calculated.

When the war concluded, a chunk of Poland as large as Czechoslovakia, an estimated 48% of its territory, was given to Belarus. My family had nowhere to return; their connection to their ancestral homeland was severed.

When people ask, “Who are your ancestors?” one answer that comes to mind for me has always included trees.

Since I was a child, I have talked to, played in, and made offerings to trees, leaving bits of flowers, chocolate, and coffee in crevices that seem hewn for just that purpose. Once, when I was 11, I got stuck halfway up a tree close to our house; to my embarrassment, my mother had to call the fire department to get me down.

When I was a child, my mother turned our backyard into a large, unruly garden. When times were difficult, I would escape to the garden and hide for hours, lying on my stomach between stalks of beans and squash.

As a young adult, I began a practice of choosing a tree ancestor, to whom I would offer small handfuls of coffee, pieces of chocolate, tobacco, and sometimes small flowers from my garden. No matter where I lived, herb collections thrived throughout even the winter months. Houseplants grew so large and unwieldy, many eclipsing my ceiling height of 14 feet, that I would have to gift them to neighbors before beginning again.

Two days ago, November 26, was World Olive Tree Day, so designated by the United Nations for the first time in 2019.

I think of what the olive trees know. The living beings, human and not, who have sheltered in their arms.

The secrets to which they have born witness.

The sorrows whispered to them for thousands of years.

The footsteps that have passed beneath them.

The earth, turning slowly.

I offer them love from their relatives, the trees in parks at the southern tip of Boston.

May they know peace and prosperity again.

If the olive tree knew [what was happening to] its planter, its oil would become tears.

Mahmoud Darwish

Sources:

Olive oil production makes up 93% of the olive harvest; the rest: Fact Sheet: Olive Trees – More Than Just a Tree in Palestine - occupied Palestinian territory | ReliefWeb. (2012, November 21). https://reliefweb.int/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/fact-sheet-olive-trees-%E2%80%93-more-just-tree-palestine

Al Badawi, arguably the oldest olive tree in the world: admin. (2018, February 16). The Palestinian Olive Tree and Ahed Tamimi. Palestine Chronicle. https://www.palestinechronicle.com/palestinian-olive-tree-ahed-tamimi/

The tree has been given numerous names over the centuries: This olive tree in Bethlehem has stood for 5,000 years—And this man is defending it. (n.d.). Middle East Eye. Retrieved November 28, 2023, from https://www.middleeasteye.net/discover/tree-trust-meet-man-guarding-palestines-oldest-olive-tree

Dr. Cesar Chelala, an Argentinian-born physician and writer living in the U.S.: Destruction of Palestinian olive trees is a monstrous crime. (2015, November 7). https://theecologist.org/2015/nov/07/destruction-palestinian-olive-trees-monstrous-crime

To replace the uprooted olive trees, the Israelis brought in European pine trees: Spangler, E. (2015). Understanding Israel/Palestine. SensePublishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-088-8

According to Sonja Karkar, founder of Women for Palestine: Destruction of Palestinian olive trees is a monstrous crime. (2015, November 7). https://theecologist.org/2015/nov/07/destruction-palestinian-olive-trees-monstrous-crime

Days after Benjamin Netanyahu’s campaign promise: Levy, G., & Levac, A. (2019, September 20). Down in the Jordan Valley, the cruel wheels of the Israeli occupation keep on turning. Haaretz. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2019-09-20/ty-article/.premium/in-the-jordan-valley-the-cruel-wheels-of-the-israeli-occupation-keep-turning/0000017f-db5a-d3ff-a7ff-fbfab4a80000

As Israeli settlements continue to expand in the West Bank, clashes: Kershner, I. (2019, February 2). As West Bank Violence Surges, Israel Is Silent on Attacks by Jews. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/02/world/middleeast/israel-west-bank-violence.html

Israeli NGO Yesh Din found that out of 211 reported incidents rsvp-khalil. (2013, October 21). October 2013 data sheet on vandalism of olive trees: Law enforcement on Israeli citizens who vandalize Palestinian-owned olive trees in the West Bank 2005-2013. Yesh Din. https://www.yesh-din.org/en/october-2013-shouldnt-it-be-2014-data-sheet-on-vandalism-of-olive-trees-law-enforcement-on-israeli-citizens-who-vandalize-palestinian-owned-olive-trees-in-the-west-bank-2005-2013-3/

“Their impact is multidimensional,” says Baha Hilo: How the West Bank’s Olive Groves Sparked a Global Movement. (2019, November 1). Time. https://time.com/5714146/olive-harvest-west-bank/

Many Jewish activists now assist the planting of new olive trees: Destruction of Palestinian olive trees is a monstrous crime. (2015, November 7). https://theecologist.org/2015/nov/07/destruction-palestinian-olive-trees-monstrous-crime

In the Himalayan region of Swat in northern Pakistan, the Taliban: Troy, J. (2019, April 1). Trees are at the heart of our country – we should learn their Indigenous names. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/01/trees-are-at-the-heart-of-our-country-we-should-learn-their-indigenous-names

In Australia, trees of great significance to Aboriginal communities continue to be destroyed: Troy, J. (2019, April 1). Trees are at the heart of our country – we should learn their Indigenous names. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/01/trees-are-at-the-heart-of-our-country-we-should-learn-their-indigenous-names

Mapuche people live in the great and ancient Araucaria forests of the southern Andes: Troy, J. (2019, April 1). Trees are at the heart of our country – we should learn their Indigenous names. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/01/trees-are-at-the-heart-of-our-country-we-should-learn-their-indigenous-names

The invaders seized capital and devastated the ecosystem, including farmland and animals: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_material_losses_during_World_War_II

Two days ago, November 26, was World Olive Tree Day: UN Calls for Protection of Olive Trees and of Palestinian Farmers Amidst Escalating Israeli Settler Violence – World Olive Tree Day 2023 | United Nations in Palestine. (n.d.). Retrieved November 28, 2023, from https://palestine.un.org/en/253865-un-calls-protection-olive-trees-and-palestinian-farmers-amidst-escalating-israeli-settler, https://palestine.un.org/en/253865-un-calls-protection-olive-trees-and-palestinian-farmers-amidst-escalating-israeli-settler

The Second Olive Tree, Mahmoud Darwish (Translated by Marilyn Hacker)

The olive tree does not weep and does not laugh. The olive tree

Is the hillside’s modest lady. Shadow

Covers her single leg, and she will not take her leaves off in front of the storm.

Standing, she is seated, and seated, standing.

She lives as a friendly sister of eternity, neighbor of time

That helps her stock her luminous oil and

Forget the invaders’ names, except the Romans, who

Coexisted with her, and borrowed some of her branches

To weave wreaths. They did not treat her as a prisoner of war

But as a venerable grandmother, before whose calm dignity

Swords shatter. In her reticent silver-green

Color hesitates to say what it thinks, and to look at what is behind

The portrait, for the olive tree is neither green nor silver.

The olive tree is the color of peace, if peace needed

A color. No one says to the olive tree: How beautiful you are!

But: How noble and how splendid! And she,

She who teaches soldiers to lay down their rifles

And re-educates them in tenderness and humility: Go home

And light your lamps with my oil! But

These soldiers, these modern soldiers

Besiege her with bulldozers and uproot her from her lineage

Of earth. They vanquished our grandmother who foundered,

Her branches on the ground, her roots in the sky.

She did not weep or cry out. But one of her grandsons

Who witnessed the execution threw a stone

At a soldier, and he was martyred with her.

After the victorious soldiers

Had gone on their way, we buried him there, in that deep

Pit – the grandmother’s cradle. And that is why we were

Sure that he would become, in a little while, an olive

Tree – a thorny olive tree – and green!