Hi readers! This qualifies as one of my ‘long reads,’ but it builds a full picture: from breaking news to deep history, science, and personal story. Feel free to pace yourself, bookmark it, or skip to sections that most speak to you. I’m honored you’re here for this conversation.

On Saturday, March 15, 2025, between the hours of 5:26 and 5:44 p.m., two planes took off from Harlingen, Texas, in defiance of a court order issued early that morning. As the planes headed south en route to El Salvador, alerts sounded in newsrooms across the United States.

A third flight followed at 7:36 p.m.

On the planes, held in shackles, were 261 immigrant detainees, among them 238 Venezuelans and 23 Salvadorans. Among them was Kilmar Abrego Garcia, whose unlawful detention has garnered attention from human rights groups worldwide.

The day before the flights took place, the president had quietly signed an executive order invoking the Alien Enemies Act, an 18th-century wartime law.

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 gives the president sweeping powers to detain and remove anyone over the age of 14 who the state defines as a “foreign national” from an “enemy nation.” (The U.S. State Department uses the term “foreign national” to mean anyone who is not a U.S. citizen, permanent green card holder, or protected person with political asylum.)

A president can invoke the Alien Enemies Act when a foreign government declares war on the United States, or threatens or undertakes an “invasion” or “predatory incursion” against the nation.

The law has been invoked only three times in U.S. history, always during a major military conflict: the War of 1812, World War I, and World War II.

As we know, the United States is not at war.

Daniel Tichenor is the Philip H. Knight Chair of Social Science at the University of Oregon and Director of the of the Wayne Morse Center’s Program for Democratic Governance. Daniel is an expert on immigration and citizenship policy and the relationship between presidential power and liberal democracy. He also writes popular pieces for The Conversation.

Tichenor calls the Trump administration’s current deportation actions “deportation on rocket fuel.”

To justify his executive order, Tichenor explained on a recent episode of the Throughline podcast, Trump has alleged that the Tren de Aragua gang is “conducting irregular warfare” on the U.S. at the direction of the Venezuelan government. He has conflated U.S. Salvadorans and Venezuelans with the nation of Venezuela, and has called for the apprehension and removal of all persons aged 14 and older whom immigrations officials deem members of the gang, using a dubious ranked score process that many gang experts say is outdated and inaccurate.

The White House has yet to provide evidence of the deportees’ membership in the Venezuelan gang.

On March 12, I covered the unlawful abduction and deportation of U.S. residents in a column entitled “The New American Gulag.”

That piece, and the column that followed it, linked the Trump administration’s establishment of zones of detention and torture that operate beyond the reaches of U.S. law to the Soviet Gulag that imprisoned between 18 and 20 million people over three decades.

On April 14, noted historian Timothy Snyder, also a Holocaust scholar and expert on authoritarianism, described these abductions and deportations using the same term: gulag.

The Trump administration is betting that the recent spate of abductions and deportations and the performative cruelty that accompanies them will distract Americans from his historically unpopular economic policies.

For over a decade, immigration has remained Trump’s ace in the hand, one he leverages to gain foreign and domestic power.

But that ace, it turns out, may be a weaker one than he’d hoped.

First, there was the revelation that Trump likely violated his pact with President Bukele of El Salvador, and the global attention to that pact by human rights groups such as the International Criminal Court, to which El Salvador is party.

Now, Trump’s approval ratings on immigration are beginning to falter.

According to a new AP-NORC poll, 46 percent of adults say that they approve of Trump's approach to immigration policy, while 53 percent disapprove—a drop of 3 percent since March. Polls conducted by CNN and The New York Times show similar results.

Immigration remains a deeply partisan issue. Among Republicans, 84 percent of adults approve of Trump’s approach to immigration policies compared to just 16 percent of Democrats.

The engine that powers Trump’s anti-immigration policies and the support they receive from his base is disinformation, false information deliberately intended to mislead others. (When spread unknowingly, it’s referred to as misinformation, which is the term most often used in scientific literature, and the one I’ll use in this piece.)

For thousands of years, people have manipulated information and media to promote their ideological and social interests. Over the past two decades, however, technology and social media have accelerated the rate at which inaccurate and harmful information can spread and take root, especially online.

This piece explores the science, psychology, and embodied experience of misinformation and how to combat it. Along the way, we’ll investigate the link between misinformation, anti-immigrant animus, and another of Trump’s executive orders on immigration that has so far flown under the radar.

Given the topic that we’re about to investigate, let me take a moment to address the elephant in the room:

Why should you trust my work? How do my professional background and personal experience support the research and writing I do here on this and other platforms?

If you’re familiar with my background and/or want to skip to the next section, click here.

To begin, I have a bachelor’s degree in behavioral sciences and a master’s in social sciences from the University of Chicago, with a focus on global geopolitics. This makes me attuned to social and political context. I have a doctorate in clinical psychology and several decades’ experience in hospital psychiatric units, outpatient group practices, and private practice, as well as supervising psychologists and social workers.

I am also a certified yoga teacher and yoga therapist. My early clinical work integrated the body into psychotherapy before focusing on the science, psychology, and practice of embodiment, a term that refers to the body’s inner senses and how they shape physical, emotional, and social well-being. I’ve written articles for popular magazines as well as peer-reviewed journals. I’ve also collaborated on research in embodiment, such as this study on the impact of interoception for attention and mental health. My Substack explores the science of embodiment, also the topic of my next book with Penguin Random House out next June.

I’m neurodivergent, and love to integrate seemingly disparate fields of study. My academic training gives my teaching and writing on science, mental health, integrative medicine, embodiment, culture, and politics a social lens. My work explores the way social factors—from dehumanization to racism to systemic oppression to immigration and other social policies—influence the body’s inner senses such as interoception, proprioception, body agency, and body ownership.

Teaching is my passion. I’ve taught on multiple topics at the intersection of science, psychology, the body, and social context at studios and in conferences in the U.S., Canada, the U.K., Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Noted historian and writer Kris Manjapra and I co-taught a course on Colonialism, Social Justice, and the Body with esteemed friend and colleague Kris Manjapra at Tufts University. I offer online courses, live masterclasses, and free webinars. (To hear about those, you can sign up for my non-Substack email list here.)

But at its root, my perspective on embodiment and social justice is deeply personal.

Illegal abduction and deportation aren’t just intellectual topics for me; they’re a core part of my immediate family history.

When my mother was 7 years old and her sisters 5 and 10, the Soviet Army invaded Eastern Poland where they lived, imprisoned my grandfather, and gave my grandmother 30 minutes at gunpoint to gather her children and a few belongings before abducting and deporting them to the Siberian Gulag. Our Jewish family living in Western Poland were sent to concentration camps, where many died. Under the Yalta Agreement that ended World War II, a portion of Poland the size of Czechoslovakia was given to the Soviets, making my family permanent refugees. After living in Uganda for 5 years, they resettled in Birmingham, England.

My own life has also been touched directly by bearing witness to forced removal. Until I was two years old, I lived with my parents on a Seneca reservation in upstate New York. In violation of the Treaty of Canandaigua signed in 1794 by 59 sachems, war chiefs, and official agents of President George Washington (and confirmed by Washington himself), President Kennedy broke his campaign promise not to build dams through this and other lands. The government ignored the solutions proposed by the Seneca and deployed the Army Corps of Engineers to force the Seneca off the land. Within a year, half the Seneca elders had died—of broken hearts, many said. This loss of community left a deep hole in my heart, and planted the seeds for speaking out against injustice.

None of these experiences confer on me a status apart from whiteness or a social positionality absent of privilege.

Yet these experiences give me an intimate familiarity with the pain and broken family lineages wrought by abduction, forced removal, dehumanization, discrimination, and loss of land. They instill in me an attunement to oppression, denial of history, and disinformation campaigns like the ones that the U.S. (under numerous presidents, not just Trump), Soviet and modern Russia, and modern Israel deploy. They make me committed to speaking out against the human rights violations that result.

I’m devoted to long-form journalism supported by multiple sources, including leading experts. To keep the main body of text clean for ease of reading, you’ll find the sources listed, APA-style, below the body of each article, with links you can click to read more.

My intention is for each meticulously cited article serve as a touchstone of information you can count on and a reference you can return to whenever you wish. No archived piece will ever be placed behind a paywall.

There’s a Topic Index on the home page of this Substack—though I confess to being perennially behind on updating it. (You’ll find a guide to a variety of articles that might interest you at the end of this piece, or at this link.)***

I hope this detour gives you the confidence that what you read here will always be fully researched, thoroughly cited, and open to commentary.

With that, let’s get to the heart of this piece.

Misinformation Drives Anti-Immigrant Sentiment

Fifty years ago, Democrats and Republicans were aligned in their views on the media, with 74 percent of Democrats and 68 percent of Republicans expressing trust.

Spurred in part by the media’s handling of the Vietnam War, trust in the media nosedived sharply over the next five decades.

According to a 2023 poll by Pew Research, the media lost ground with every main political group in the U.S.

Meanwhile, the small partisan divide widened into a gaping chasm. Only 58 percent of Democrats said they trusted the media, while only 11 Republicans said the same.

This growing mistrust in the media sets the stage for disinformation and misinformation to spread.

Strikingly, there is also a wide partisan divide in the sharing of misinformation.

This seems to be common knowledge. Whenever I post on social media about abduction, deportation, exile, or other social and political issues, people predict that even the most thoroughly sourced piece or diligent fact-checking will make little difference to Trump’s followers. “They just don’t care about accuracy,” people say.

The data happens to confirm this. People with extreme political attitudes, especially those on the far-right of the political spectrum, share a disproportionate amount of online misinformation.

What underpins the sharing of misinformation among conservative and far-right individuals?

Until recently, both scientific and popular thought held that people who share misinformation do so because they don’t pay attention to whether or not it’s true.

And yet, emerging research suggests a more complex dynamic.

At the Social Brain Lab in Barcelona, Clara Pretus and her colleagues study the factors that drive people to support far-right parties. In 2023, Pretus and her team conducted a trio of elegant experiments to examine how political values and identity influence the spread of misinformation among conservative and far-right partisans in both the U.S. and Spain.

The experiments brought to life with startling clarity the “stickiness” of misinformation that frustrates so many of us.

Misinformation is most durable, it turns out, when it relates to “sacred” values—that is to say, deeply held core values and identities that matter the most to voters.

For both far-right and center-right voters, core values include immigration, nationalism, and family values.

In Spain, popular interventions such as fact checks and accuracy nudges did not significantly lower the likelihood of sharing misinformation among either center right or far-right voters.

In the United States, Trump is the lever that sends this pattern into overdrive.

Republican voters in the U.S. whose political identifies were “fused” with Trump were more likely to share misinformation than other Republicans, particularly when that misinformation related to their deeply held beliefs. Importantly, even Republican identity without Trump at its center predicted a higher likelihood of sharing misinformation, regardless of the values involved.

Strikingly, while Twitter fact-checks reduced the likelihood of misinformation sharing among U.S. Republicans, those checks had no effect on Republicans fused with Trump. This particular group showed a marked resistance to interventions against misinformation; this was true even when other Republicans considered the information implausible.

“Sharing misinformation on core partisan values has an important social signaling function, allowing group members to show others that they belong,” Pretus said in an interview. This kind of social accuracy, she added, signals that they’re in tune with the group.

Social approval transforms misinformation into an emblem of belonging, making it impervious to most popular interventions, the ones so many of us try to implement.

This paints a sobering picture—though fortunately not an immutable one—of the stubborn resilience of misinformation sharing.

For center-right and far-right voters, social accuracy trumps factual accuracy.

This insight also holds the key to changing this influential pattern.

Pretus and her colleagues wondered if it were possible to employ identity-based interventions that leveraged social connection to reduce misinformation.

In a novel follow-up study, they incorporated social cues directly into the social media user interface to promote accuracy of information sharing.

Across three experiments in the U.S. and the U.K., they crowdsourced accuracy judgments. Next to the “Like” count, they added a “Misleading” count that reflected the norms of users’ social in-group such as Republicans or Democrats. This reduced participants’ likelihood of sharing inaccurate information about partisan core values (e.g. immigration) by an impressive 25 percent.

The “social norm” intervention was five times as effective as popular misinformation tools like accuracy nudges, which reduced information sharing by only 5 percent.

In polarized contexts like the U.S., identity-based interventions based on social norms and belonging can be more effective than neutral, cognitive ones in countering partisan misinformation.

How Embodiment Helps Us Cope with Polarization

What about those of us on the center-to-left end of the spectrum? What can we do to manage the stress we experience in a time of intense political polarization, when the diligent work we do to resource information seems to have no discernible effect?

This is where the science of embodiment comes into play.

In 2024, a group of researchers based in London set out to investigate whether attunement to sensations and feelings that arise in the body, also known as interoception, can lessen the negative impact of politics on our health. (For more on the impact of interoception on emotional and social health, click here. And for more on interoception as a practice in today’s social world, see this piece.)

In a sample of both U.S. Republicans and Democrats, interoception helped to counteract the adverse effects of political engagement on citizens’ health irrespective of party allegiance. Critically, the study authors noted interoceptive attunement did not impact political engagement and participation, but acted as a protective “buffer” that made people more likely to be politically engaged.

This study and the Pretus studies are part of an emerging field called visceral politics. This fascinating field studies topics: the moral language of U.S. presidential campaigns, for instance. Or who has a stronger connection to bodily signals—liberals or conservatives? Or the way anger, even the non-political kind, makes people more likely to vote for authoritarian leaders. (I interviewed one of the field’s leading researchers for this article on the influence of media reportage on the way we view refugees.)

We can also leverage the connection we have with our bodies to reduce our own sharing of misinformation. The media and popular culture often speak about the strong draw of outrage and polarization, which makes us more likely to share information that has those qualities.

To my mind, stopping ourselves from sharing misinformation is difficult in large part because to do so creates sensory and emotional “friction” (think discomfort and arousal) in much the same way as resisting other compelling habits (like scrolling on social media). When we resist the impulse to share immediately, or undertake the arduous process of double-checking sources, we experience agitation. Becoming familiar with our own particular visceral “signature” or flavor of this friction, and leaning into it over time, builds the sensory resilience we need to boycott misinformation ourselves.

As I sifted through the research on misinformation sharing, one pressing question continued to resurface.

What makes immigration so important to center- and far-right Republicans, especially those whose identities are “fused with Trump?”

The answer lies in an executive order Trump signed on February 7, 2025, less than three weeks after taking office.

This executive order is a striking example of the ways in which disinformation, racial panic, and immigration policy collide.

One Group Gets A Clear Path to Asylum

The order, titled “Addressing Egregious Actions of The Republic of South Africa,” directed US agencies to halt aid to South Africa, a dictate that earned global condemnation.

It also denounced South Africa for bringing a genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), calling this an “aggressive position” that undermines U.S. foreign policy. (Strikingly, this language directly mirrors the government’s justification for abducting and detaining pro-Palestinian activists Mahmoud Khalil, Rumesya Ozturk, and Mohsen Mahdawi, the latter of whom was released.)

But the third part of the executive order has largely flown under the public radar.

While one of Trump’s first actions as president halted the arrival of Black and Brown refugees into the U.S., this one gives one racial group—white South Africans—a clear path to U.S. asylum.

We are bearing witness to mass abduction and deportation of U.S. residents fleeing real persecution in other countries on the one hand—and asylum for white Afrikaners fleeing imagined persecution in South Africa on the other.

To justify this racial asymmetry, the U.S. government cites the far-right conspiracy theory endorsed by Trump, Elon Musk, and others, falsely claiming that white South African farmers endure unjust racial discrimination and government-sanctioned violence, and are at imminent risk of “genocide” at the hands of Black South Africans.

However, a land audit by the South African government in 2018 found that white people comprise 7.2 percent of the population but hold approximately 72 percent of all privately owned farmland. South Africa’s 1996 constitution requires that land dispossession resulting from colonialism must be addressed as an urgent moral priority, and it has taken steps to remedy the land dispossession caused by decades of apartheid. These conspiracy theories aim to present white farmers as victims.

The government’s executive order also echoes the antisemitic and racist Great Replacement Theory, which alleges that Jewish, Black, and Brown immigrants and residents are “poisoning the blood of the nation,” are “terrorists,” or intend to “rape or kill” U.S. citizens. The theory also contends that liberal and progressive politicians deliberately seek to change U.S. demographics by replacing conservative white voters with their Black, Brown, and progressive Jewish counterparts.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, nearly 7 in 10 Republicans surveyed endorse the belief that changing U.S. demographics are linked to deliberate attempts to replace them with liberal and progressive voters.

To this group of people, equality feels like persecution. Loss of power feels like an existential death—and therefore, like “genocide.”

Linked directly with the Great Replacement Theory, the Trump administration’s reliance on disinformation to refer to migration across the U.S.-Mexico border as an “invasion” and those seeking asylum as “terrorists” has seeped into dozens of pieces of anti-immigration legislation and aided the misinformation argument that migrants are flowing into the U.S. to commit large-scale voter fraud.

On one side, Trump casts entire nations in the Global South as existential threats, justifying mass deportations under the pretext of war. On the other, he offers refuge to white South Africans, portraying them as imperiled minorities under Black governance.

The administration frames Black and Brown bodies as enemy combatants and white bodies as endangered victims.

This is a deliberate strengthening of the U.S. racial caste system, which elevates whiteness as deserving of protection and casts Black and Brown people as hostile, invading forces.

This is a racial importation policy designed to shore up a “threatened” white demographic inside U.S. borders. It is a tool of population engineering to shape the nation’s racial and genetic future—a kind of eugenics 2.0.

Some white South Africans have jumped at the chance to move to the U.S. But the majority of white South Africans have said, in no uncertain terms, “no thanks.”

My favorite of the intelligent repartees to Trump’s offer, penned by Max Du Preez, is anthemic, humorous, and honest. (I highly recommend reading it in its entirety.)

In an op-ed piece for the Guardian, Du Preez resists this misinformation. He states,

“Just for the record: Afrikaners are generally better off today than prior to 1994, when they gave up political power; materially, culturally and in terms of personal freedom.

South Africa’s progressive constitution with its extensive bill of rights is intact; the rule of law is maintained and the judiciary is independent and functioning; we are a genuinely open society with free speech and media that many other democracies, especially Trump’s America, can be jealous of.

Whites (about 7.3% of the population) still dominate the economy and own about half the land—and not one square inch of it has been confiscated from white owners. White unemployment stands at 7% with the national figure at more than 30%. The crime rate in the predominantly white suburbs is minuscule compared with that in the vast black townships.”

Where does all this leave us?

I reached out to Daniel Tichenor, an expert on immigration law and policy, including the Alien Enemies Act. Daniel warned me about the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952—the one mentioned above that has given Trump and his cabinet significant leverage to go after any noncitizens whose speech they deem inconsistent with U.S. foreign policy interests. (Think here of the government’s actions against the nation of South Africa and individuals like Rumesya Ozturk and Mahmoud Khalil.)

I knew this act intimately; it was the one that delayed my mother’s U.S. citizenship application for 15 years, due to quotas for Eastern European immigrants. (I’ll cover the act and its implications in another column.)

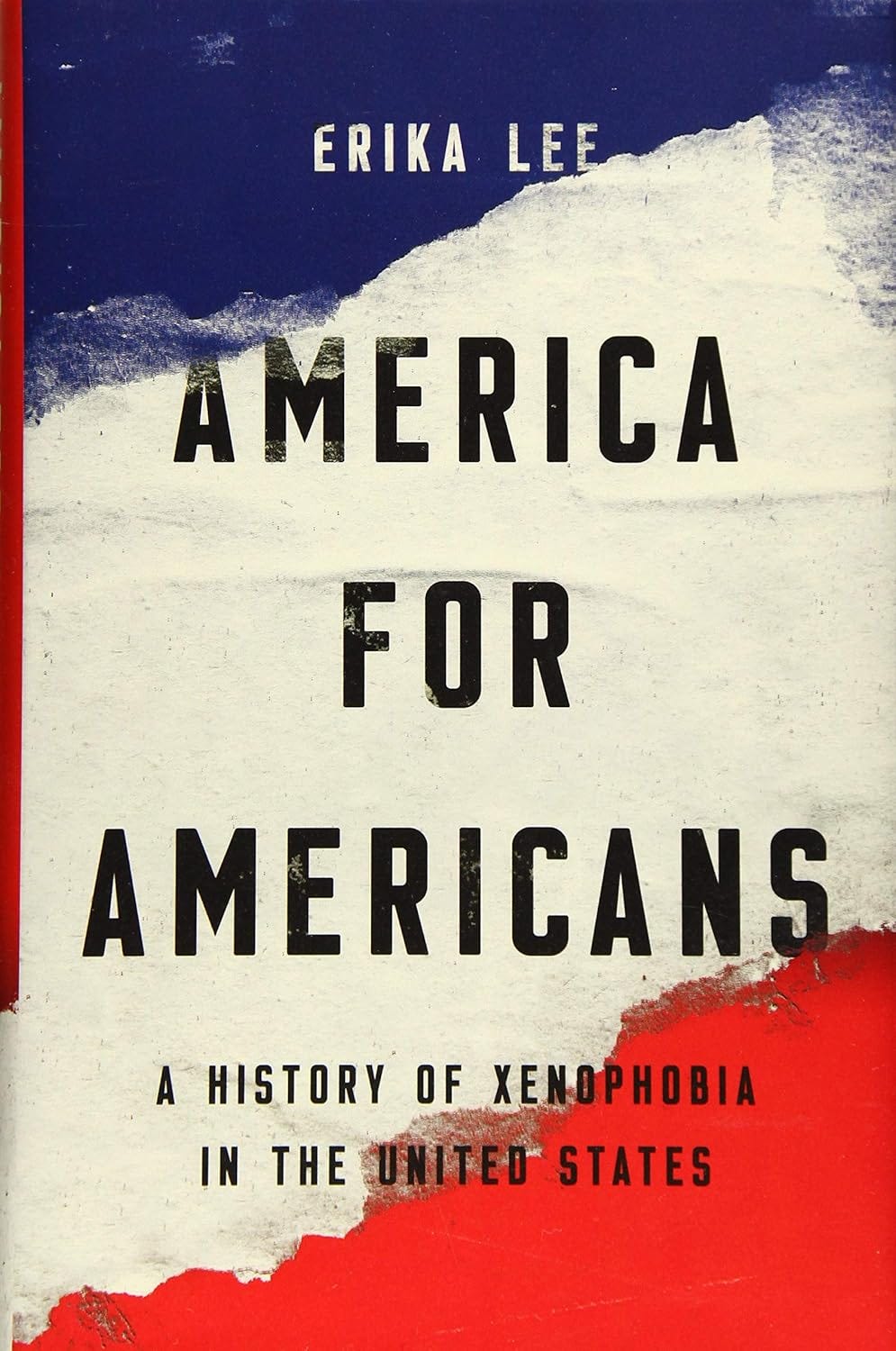

Daniel wrote eloquently about the the weight of xenophobia, and the way it makes us afraid to live our lives—but also of the courage we have in resisting it. He recommended Erika Lee’s groundbreaking work on xenophobia. (Lee has an award-winning book, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States, and a popular TED Talk.)

Lee says about xenophobia,

“One of the most important things about xenophobia is that it’s a shapeshifting, wily thing, just like racism. You think it’s gone away, and it comes back. It evolves so that even though one immigrant group finally gains acceptance, it can easily be applied to another.

And sometimes the group that just made it can be very active in leading the charge against the others. It’s unfortunately one of the ways in which racism and our racial hierarchy are at work in the United States.”

One way to overcome the alienation that xenophobia brings is to combat the negative stereotypes about immigrants and refugees, and help see them as fellow human beings just like us, Lee says. She leads an effort to do just that, with the Immigrant Stories digital storytelling project. Funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the project’s 350 digital stories profile immigrants as “real people, not stereotypes,” she says.

Final Reflections:

The identity of Jewish and Polish people is inextricably bound with exile, as it is for so many others. I believe that to force another people into exile—Ukrainians, Palestinians, Sudanese, South or Central Americans—is a crime against humanity. It violates human sovereignty and self-determination. It also violates the tenets of the Jewish faith, which call for embracing the ger (stranger) among us and for standing up in solidarity with our shared humanity and the civil rights denied to many of us.

As my esteemed colleague Katherine Hartsell wisely puts it, we can “practice” humanization with intention. We can do so by reading and sharing immigrant stories, recalling the hardships of our ancestors, resisting the spread of misinformation, and fighting dehumanization.

As we close, I’d like to share with an example of humanizing practice from my father, who is one of my greatest teachers.

Dad served in the Third Armored “Spearhead” Division that liberated the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp near the end of World War II. The atrocities he witnessed there, many of which he documented on camera for the U.S. Army, haunted him for the rest of his life and drove him to become a Holocaust scholar.

As many of you know, everyday German citizens were widely seen as complicit in the atrocities committed by the Nazis—and to some extent, still are today.

The U.S. media initiated a widespread misinformation campaign to paint the German people as hostile and complicit.

It would have been so easy, so frictionless, for Dad to corroborate and share that misinformation, to “other” the German people as many have done—and some still do. But Dad wasn’t having any of it.

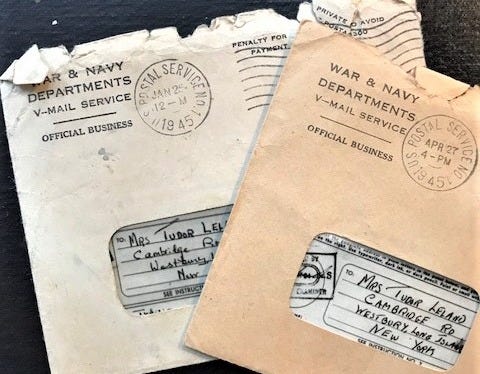

While I’d always known of his love for the German people, language, and culture, I’d never understood the act of humanizing—and resistance to misinformation—this love required. But several years after his death, I found a package on my doorstep from his sister Phyllis, also my aunt.

In that package were dozens of letters he wrote her, some typed on paper and others in his own handwriting, from the front in Europe. Each one was accompanied by black-and-white photographs of the countryside, tanks, and people with whom he was stationed.

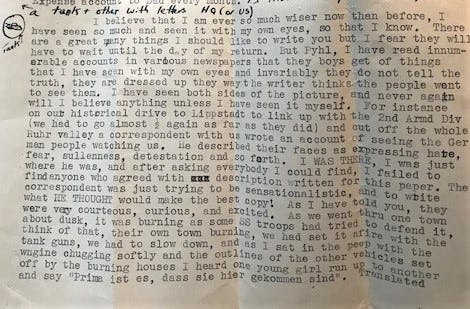

One letter in particular caught my eye. Penned on June 6, 1945, it refers directly to the misinformation levied against the German’s by U.S. media, and to Dad’s own response.

Dad wrote,

“I have read innumerable accounts in various newspapers that the boys get that I have seen with my own eyes and invariably they do not tell the truth, they are dressed up the way the writer thinks the people want to see them. I have seen both sides of the picture, and never again will I believe anything unless I have seen it myself.

For instance, on our historical drive to Lippstadt to link up with the Second Armored Division, we had to go almost half again as far as they did. And out of the whole Ruhr Valley a correspondent with us wrote an account of seeing the German people watching us. He described their faces as expressing hate, fear, sullenness, detestation and so forth. I WAS THERE. I was just where he was, and after asking everybody I could find, I failed to find anyone who agreed with the description written for [redacted] newspaper. The correspondent was just trying to be sensationalist, and to write what HE THOUGHT would make the best copy! As I have told you, they [the German people] were very courteous, curious, and excited.

As we went through one town about dusk, it was burning as some SS troops had tried to defend it. Think of that: their own town burning, we had set it afire with the tank guns, we had to slow down. And as I sat in the peep [sic] with the engine chugging softly and the outlines of the other vehicles set off by the burning houses I heard one girl run up to another and say, “Prima ist es, dass sie hier gekommen sind.” Translated, that means, “Isn’t it swell that they have come.” Nothing makes me madder than to read the deliberate lies written in the papers back home.”

Dad was just 26 years old when he had that insight.

The Power of Individual and Collective Resistance

Alongside the weight of history and its long trail of human rights abuses, there are small signs of resistance.

These signs portend a movement against Trump’s modern American Gulag, and the racial caste it seeks to reinforce.

On May 1, 2025, Trump-appointed federal judge Fernando Rodriguez Jr., of the Southern District of Texas. Judge Rodriguez ruled that the president’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act exceeded the scope of the law and contradicts the “plain, ordinary meaning” of its terms.

On April 26, ultraconservative Fox News analyst Karl Rove delivered a scathing critique of Trump’s policies, particularly on immigration, in a high-profile interview on Fox News.

On May 5, the New York Times reported on a newly declassified memo from multiple U.S. intelligence agencies that directly contradicts Trump’s invocation of the Alien Enemies Act. The memo corroborates intelligence findings reported by The New York Times in March; it states that these U.S. intelligence agencies do not believe that the administration of Venezuela’s president, Nicolás Maduro, controls a criminal gang, Tren de Aragua. The intelligence community had circulated findings on Feb. 26 that reached the opposite conclusion. After The Times published its article, the Justice Department opened a criminal investigation and portrayed the Times’ reporting as misleading and harmful.

On May 6, A United States judge in Boston ordered a temporary block on the Trump administration's plan to deport migrants to Libya, saying it would "clearly violate" his prior order ensuring migrants’ right to due process.

On May 7, Brazil turned down the U.S. government’s request to designate two gangs as terrorist organizations, and to accept U.S. deportees from these countries.

Also on May 7, Libya’s two rival governments on Wednesday denied any agreement to accept migrants from the U.S., disrupting Trump administration plans to fly deportees there.

The arc of the story is still in progress, and public resistance will help give it shape.

Want to read more? Try these articles on emerging research in the field of integrative medicine, such as innovations in mental health, neurobiology, ADHD, menopause, neurodegenerative disease, and immunology. or this piec on social justice. You can also check out the Topic Index for more.

Sources:

On Saturday, March 15, 2025, between 5:26 and 5:44 p.m.: Times, T. N. Y. (2025, April 30). Timeline: How the Administration Deported Migrants Despite Judge’s Order. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/04/30/us/politics/trump-venezuela-deportations-timeline.html

On the planes, held in shackles, were 261 immigrant detainees: Tracking Trump and Latin America: Migration—Judge Rules Against Use of Alien Enemies Act | AS/COA. (2025, May 1). https://www.as-coa.org/articles/tracking-trump-and-latin-america-migration-judge-rules-against-use-alien-enemies-act

The day before the flights took place, the president had quietly signed: Invocation of the Alien Enemies Act Regarding the Invasion of The United States by Tren De Aragua. (2025, March 15). The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/invocation-of-the-alien-enemies-act-regarding-the-invasion-of-the-united-states-by-tren-de-aragua/

The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 gives the president sweeping powers to: 9339. (2024, October 16). The Alien Enemies Act, Explained | Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/alien-enemies-act-explained

The U.S. State Department uses the term “foreign national” to mean: What is the Department of State’s definition of a foreign national? (Mississippi State uses the term “non-U.S. person”) | Office of Research Compliance & Security. (n.d.). Retrieved May 2, 2025, from https://www.orc.msstate.edu/faq/what-department-states-definition-foreign-national-mississippi-state-uses-term-non-us-person

A president can invoke the Alien Enemies Act when a foreign government declares war: 9339. (2024, October 16). The Alien Enemies Act, Explained | Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/alien-enemies-act-explained

The law has been invoked only three times in U.S. history, always: 9339. (2024, October 16). The Alien Enemies Act, Explained | Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/alien-enemies-act-explained See also: Tichenor, D. (2025, March 17). Trump is using the Alien Enemies Act to deport immigrants – but the 18th-century law has been invoked only during times of war. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/trump-is-using-the-alien-enemies-act-to-deport-immigrants-but-the-18th-century-law-has-been-invoked-only-during-times-of-war-252434

Now, Trump’s approval ratings on immigration are beginning to falter: Since the beginning of 2025, approval of President Trump’s handling of immigration has softened slightly | Ipsos. (2025, April 25). https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/abc-news-washington-post-ipsos-april-2025

According to a new AP-NORC poll, 46 percent of adults say that they approve: Yoder, J. (2025, April 25). Immigration remains one of Trump’s strongest issues—AP-NORC. https://apnorc.org/projects/immigration-remains-one-of-trumps-strongest-issues/, https://apnorc.org/projects/immigration-remains-one-of-trumps-strongest-issues/

Polls conducted by CNN and The New York Times show: Edwards-Levy, A. (2025, April 30). CNN Poll: Majorities oppose Trump deporting migrants to Salvadoran prison, canceling international student visas | CNN Politics. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2025/04/30/politics/trump-poll-immigration-deportations/index.html See also: Goldmacher, S., Igielnik, R., & Baker, C. (2025, April 25). Voters See Trump’s Use of Power as Overreaching, Times/Siena Poll Finds. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/25/us/politics/trump-poll-approval.html

Among Republicans, 84 percent approved of the president's immigration policy, compared: Polls show President Trump losing support on immigration policies. (2025, April 28). Scripps News. https://www.scrippsnews.com/politics/immigration/polls-show-president-trump-losing-support-on-immigration-policies

The White House has yet to provide evidence of the deportees’ gang membership: US deports hundreds of Venezuelan immigrants despite court order. (2025, March 16). France 24. https://www.france24.com/en/americas/20250316-trump-deports-immigrants-venezuela

I covered the recent unlawful abductions and deportations of U.S. residents: Forbes, B. (2025, March 12). The New American Gulag [Substack newsletter]. Bodies of Knowledge. https://boforbes.substack.com/p/the-new-american-gulag

On April 14, noted historian Timothy Snyder, who is also a Holocaust scholar and expert: Snyder, T. (2025, April 14). Trump: “Home-growns are next” [Substack newsletter]. Thinking About...

These policies depend on disinformation, false information deliberately: Disinformation. (n.d.). Shorenstein Center. Retrieved May 3, 2025, from https://shorensteincenter.org/research-initiatives/disinformation/ See also: Misinformation and disinformation. (n.d.). Https://Www.Apa.Org. Retrieved April 29, 2025, from https://www.apa.org/topics/journalism-facts/misinformation-disinformation

Fifty years ago, Democrats and Republicans were aligned in their views: Media Mistrust Has Been Growing for Decades—Does It Matter? (2024, October 17). https://pew.org/3Nl4wYc

Only 58 percent of Democrats said they trusted the media, while only 11 percent: Media Mistrust Has Been Growing for Decades—Does It Matter? (2024, October 17). https://pew.org/3Nl4wYc

People with extreme political attitudes, especially those on the far-right: Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science, 363(6425), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706 See also: Pretus, C., Servin-Barthet, C., Harris, E. A., Brady, W. J., Vilarroya, O., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2023). The role of political devotion in sharing partisan misinformation and resistance to fact-checking. Journal of experimental psychology. General, 152(11), 3116–3134. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001436

In 2023, Pretus and her team conducted a trio of elegant experiments: Pretus, C., Servin-Barthet, C., Harris, E. A., Brady, W. J., Vilarroya, O., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2023). The role of political devotion in sharing partisan misinformation and resistance to fact-checking. Journal of experimental psychology. General, 152(11), 3116–3134. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001436

Sharing misinformation on core partisan values has an important social signaling: Dolan, E. W. (2023, July 30). Neuroimaging study provides insight into misinformation sharing among politically devoted conservatives. PsyPost - Psychology News. https://www.psypost.org/neuroimaging-study-provides-insight-into-misinformation-sharing-among-politically-devoted-conservatives/

In a novel follow-up study, Pretus and colleagues developed an intervention: Pretus, C., Javeed, A. M., Hughes, D., Hackenburg, K., Tsakiris, M., Vilarroya, O., & Van Bavel, J. J. (n.d.). The Misleading count: An identity-based intervention to counter partisan misinformation sharing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 379(1897), 20230040. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2023.0040

In 2024, a group of researchers based in London set out to investigate whether attunement to sensations and feelings: Mohr, M. V., & Tsakiris, M. (2024). Feeling the body politic: The relationship between interoception and the impact of politics on our health. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/nbmep (Note: You can download the pdf here: https://osf.io/nbmep/download/?format=pdf)

This study and the Pretus studies are part of an emerging field: Politics is in peril if it ignores how humans regulate the body | Aeon Essays. (n.d.). Aeon. Retrieved May 4, 2025, from https://aeon.co/essays/politics-is-in-peril-if-it-ignores-how-humans-regulate-the-body

But this particular order did the opposite: It gave one racial group a clear: Addressing Egregious Actions of The Republic of South Africa. (2025, February 8). The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/02/addressing-egregious-actions-of-the-republic-of-south-africa/

Strikingly, this language directly mirrors the government’s justification for abducting and detaining: Pressed for evidence against Mahmoud Khalil, Rubio argues his presence undermines U.S. foreign policy. (2025, April 10). PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/pressed-for-evidence-against-mahmoud-khalil-rubio-argues-his-presence-undermines-u-s-foreign-policy

This rhetoric directly echoes a conspiracy endorsed by both Trump and Elon Musk: Cocks, T., Peyton, N., Hesson, T., Cooke, K., Cocks, T., Peyton, N., Hesson, T., & Cooke, K. (2025, April 24). US focuses on persecution claims as white South Africans seek resettlement. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/us-focuses-persecution-claims-white-south-africans-seek-resettlement-2025-04-24/ See also: Carter, S. (2025, March 10). What’s the truth behind Trump offering White South African farmers U.S. citizenship? - CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-south-africa-farmers-white-afrikaners-offer-us-citizenship/ See also: Kanno-Youngs, Z., & Aleaziz, H. (2025, March 30). ‘Mission South Africa’: How Trump Is Offering White Afrikaners Refugee Status. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/30/us/politics/trump-south-africa-white-afrikaners-refugee.html See also: Trump suspended the refugee program. Why is he inviting white South Africans to find a new home in the U.S.? (2025, April 22). PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/trump-suspended-the-refugee-program-why-is-he-inviting-white-south-africans-to-find-a-new-home-in-the-u-s

The government’s executive order also echoes the antisemitic and racist Great Replacement Theory: Project 2025, Immigration, Great Replacement 2024 National Poll—October 29, 2024: Department of Political Science: UMass Amherst. (n.d.). Retrieved May 6, 2025, from https://www.umass.edu/political-science/about/reports/2024-12 See also: Schiavenza, M. (2024, November 1). Deep Dive: The Great Replacement Theory. HIAS. https://hias.org/news/deep-dive-great-replacement-theory/ See also: Coates, R. (2024, March 15). What is the ‘great replacement theory’? A scholar of race relations explains. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/what-is-the-great-replacement-theory-a-scholar-of-race-relations-explains-224835

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, nearly 7 in 10 Republicans surveyed: Racist ‘Replacement’ Theory Believed by Half of Americans. (2022, June 1). Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/stories/poll-finds-support-great-replacement-hard-right-ideas/ See also: Popli, N. (2022, May 16). How the ‘Great Replacement Theory’ Has Fueled Racist Violence. TIME. https://time.com/6177282/great-replacement-theory-buffalo-racist-attacks/

Some white South Africans have jumped at the chance to move: Savage, R. (2025, April 30). The white Afrikaners lining up to accept Trump’s offer of asylum. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/apr/30/a-godsend-the-white-afrikaners-lining-up-to-accept-trumps-offer-of-asylum

But the majority of white South Africans have said, in no uncertain terms: Trump says some white South Africans are oppressed and could be resettled in the US. They say no thanks. (2025, February 8). AP News. https://apnews.com/article/trump-south-africa-afrikaners-0120efec17122b47e3371e0e39fe1db8

My favorite of the intelligent repartees to Trump’s offer, penned by Max Du Preez: Preez, M. du. (2025, April 6). As a white Afrikaner, I can now claim asylum in Trump’s America. What an absurdity. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/apr/06/white-afrikaner-donald-trump-america-us-administration

Daniel Tichenor, the Philip H. Knight Chair of Social Science: https://news.uoregon.edu/expert/daniel-tichenor-department-political-science

Tichenor calls the Trump administration’s current deportation actions: The Alien Enemies Act: Throughline. (2025, April 17). NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/04/17/1245273514/alien-enemies-act

On May 1, 2025, Trump-appointed federal judge Fernando Rodriguez Jr.: Trump-appointed federal judge rejects use of Alien Enemies Act in Venezuelan deportations. (2025, May 1). NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/trump-appointed-federal-district-judge-rejects-use-alien-enemies-act-v-rcna204150

On May 7, Brazil turned down the U.S. government’s request to designate: Reuters. (2025, May 7). Brazil rejects US request to designate two gangs as terrorist organizations. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/may/07/brazil-gangs-terrorist-designation-pcc-comando-vermelho

On May 6, A United States judge in Boston ordered a temporary block: Tondo, L., Helmore, E., & Mackey, R. (2025, May 7). US reportedly planning to deport migrants to Libya despite ‘clear’ violation of court order. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/may/07/us-planning-to-deport-migrants-to-libya-despite-hellish-conditions-reports

Also on May 7, Libya’s two rival governments on Wednesday denied: Ward, J. M., Mariah Timms and Alexander. (2025, May 8). Libya’s Leaders Say They Haven’t Agreed to Accept Deported Migrants From the U.S. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/politics/policy/libyas-leaders-say-they-havent-agreed-to-accept-deported-migrants-from-the-u-s-c28ffd05