Following a stroke, a woman can see and feel her left arm, but believes that it belongs to her partner.

After a deadly shark attack that claims his right arm and leg, a Navy Seal contends with phantom limb pain, and with the sense that his prosthetic limbs are not yet part of his body.

And in therapy, a woman describes feeling detached from her body, almost though she’s observing the movements and actions of someone else.

These experiences may seem radically different, yet they’re united by one common thread. They all involve body ownership, the sense that the body we’re in belongs to us—that it is our body that feels and moves.

Body ownership is one of our primary inner senses and a key node of embodiment. It may sound automatic, even facile, but it’s not. As one philosopher-scientist pointed out, the body that you experiences is always your own, but that doesn’t mean that you always experience it as your own.

There’s a field of science, scholarship, philosophy, and activism that revolves around what body ownership is, how it works, and why it matters. Let’s take a closer look.

The Rubber Hand Illusion

One way that researchers learn about sensory systems is to study what happens when something compromises them: in the case of body ownership, when part or all of our body doesn’t feel like it belongs to us.

This was the case with each of the people above: The woman who believed that her left arm belonged to her partner had somatoparaphrenia, a post-stroke syndrome in which a limb feels like someone else’s. The Navy Seal experienced a common side-effect of limb loss: his brain hadn’t yet accepted the prosthesis as part of his body. And the woman in therapy had an experience many of us can relate to: depersonalization, a sense that we’re removed from our bodies, ghosting through life and observing our actions and feelings from the outside.

So what has helped scientists understand this special sense more deeply?

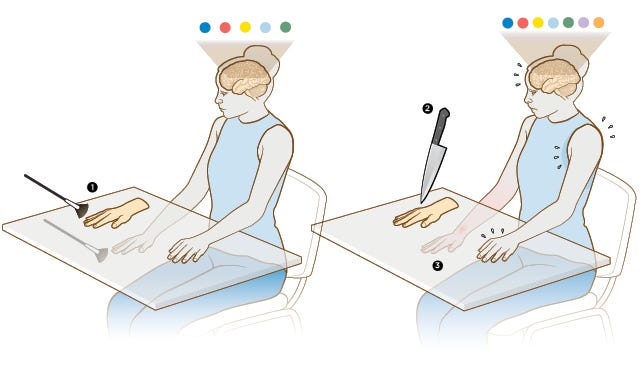

Enter the Rubber Hand Illusion, developed in 1998 by Jonathan Cohen and Matthew Botvinick. The researchers placed a rubber hand in front of participants while having them hide their real hands behind a screen. They stroked the rubber hand and the real unseen hand with a small paintbrush at the same time and in the same tempo. (The other real hand rested at a distance, untouched.)

Within a couple of minutes, the participants reported “feeling” the brushstrokes on the rubber hand. They had accepted the rubber hand as part of their bodies. Importantly, the illusion does not occur when the rubber hand and real hand are stroked at different tempos.

The illusion allows scientists to manipulate body ownership in a laboratory setting, and then study both the brain and the direct experience of ownership.

The study incited a revolution in modern neuroscience, and spawned over 5,000 research papers. Since then, researchers have developed many other illusions. These include an out-of-body illusion which makes people feel as though they’re watching their body from behind, or that they’re in the body of another person. There’s “Barbie” illusion that makes people feel that they’re in a miniature body. And there’s even an analogue in mice, aptly termed the Rubber Tail Illusion.

What do these illusions tell us about the science and experience of body ownership?

The Bodily Self + the Immune Self

A central insight of the Rubber Hand Illusion is that the brain has a stable body schema, a representation of our body and its parts. During the brief time period of the Rubber Hand Illusion, the body schema doesn’t allow for the existence of three hands. (That would take the brain more time and effort to accommodate.)

This means that to adopt a rubber hand as our own, we have to disown the hand that is ours.

When we do, there are consequences. One involves proprioception: The illusion makes us locate our real hand closer in space to the rubber one, an effect called proprioceptive drift. But that’s not all.

Researchers investigated what happens to the disowned hand—the one we relinquish in order to adopt the rubber hand. They found several effects. During the illusion, for instance, body temperature dropped—but only in the disowned hand (not the rest of the body)—a change that suggests reduced blood flow. The researchers concluded that our conscious sense of our bodily self and the regulation of this self are connected. Other studies found additional changes, including a release of histamines in the disowned hand and arm. And studies show that when the rubber hand is threatened, people experience a stress response.1

My take: Consider for a moment the question our immune system poses: What is me, and what is not me? When it encounters a foreign invader (viruses, bacteria, or fungi), the immune system launches an alarm response that attacks the invader. In the Rubber Hand Illusion, the brain and body mount an alarm response of their own to the disowning of the hand, and physiological dysregulation occurs.

This causes me to wonder: If these are the consequences of limb disownership for the brief duration of a scientific experiment, what happens in prolonged disownership, the kind that occurs in dissociation and disembodiment?

Body Ownership as a Boundary Issue

In much the same way as the immune system, body ownership involves the inquiry, “What is mine or me, and what is not?” Body ownership helps create boundaries between ourselves, others, and the world around us.

It might sound like we’d never want to accept a foreign object as part of our bodies, but that’s actually not the case.

Healthy bodily and interpersonal boundaries require both stability and flexibility. We need a stable sense of our bodies to feel rooted and grounded. Yet we also need the capacity to adapt in response to the changing world around us.

In fact, in some syndromes such as anorexia, people are more vulnerable to the Rubber Hand Illusion—in other words, their bodily sense of bodily is more malleable to external influences like vision and social stimuli. (The same is true in depersonalization.) This makes sense, because research people with eating disorders also have a weaker sense of interoception. How, exactly, do the two—interoception and body ownership—relate?

Body Ownership As An Act of Resistance

The Rubber Hand Illusion illuminates the contrast between our five outer senses, particularly vision, and our inner ones, like interoception (the ability to receive signals that come from the body), proprioception, and body agency.

In the Rubber Hand Illusion, vision (an outer sense) eclipses interoception, proprioception, and body (inner senses). Put another way, what we see is stronger than what we feel and where we feel our hand located in space. And it turns out that people with a lower sense of interoception showed a greater inclination to adopt the rubber hand as their own. This suggests that in the absence of accurate interoception, our sense of self is determined by exteroception and the outer senses.

We could extend this understanding to say that in the absence of a strong connection to the inner world of our bodies, our sense of body and self are determined by the stimuli of outside forces. Think advertising, media, social media, and other dominant cultural norms—which, like the Rubber Hand Illusion, center on the outer sense of vision.

Body Ownership + Our Larger Social Body

We use the term “body ownership” often to describe the inalienable right to feel that our bodies belong to us.

Body ownership writ large is the freedom to make decisions about what happens to and in our bodies.

Think of social justice and equity: the way systemic racism and oppression find myriad ways to violate body ownership. They do this through excess surveillance, police brutality, mass incarceration, a history of forced medical procedures and involuntary sterilization, and an infringement of voting rights (which underlie the ability to determine laws that shape bodily ownership and bodily self-determination).

Consider body sovereignty and consent: the way body ownership underpins the right to determine what happens to our bodies and what we agree to do with them in regard to pleasure, sexuality, and gender expression. (Consider especially the prevalence of sexual harassment, sexual assault, gender-related violence, and sexual abuse—and the difficulty we have as a culture guarding against, acknowledging, and repairing them.)

This is one reason why sexual assault and gender-based trauma are so insidious: They attack body agency and body ownership simultaneously, and attempt to attack interoception and proprioception, even if (contrary to what popular thinking on trauma may say) many trauma survivors have a high degree of interoception.

Think of abortion rights: the way they’re tied to healthcare, and the myriad ways that patriarchal structures attempt to take ownership over vulnerable bodies.

Think of disability justice, which challenges ableist norms and promotes inclusive narratives of body ownership.

Developing Deeper Body Ownership

A vast body of work establishes body ownership as a multisensory element that combines touch, interoception, proprioception, and body agency.

In fact, many researchers say, body agency is a condition for body ownership: Experiences of agency, of moving and acting over time, give rise to the sense of body ownership, of the body as me or mine.)

You could think of this relationship in terms of the equation, “body agency + body ownership = body sovereignty”

So how, exactly, do we increase body ownership?

One of the best ways to do so may be connective tissue (fascia) self-massage. Fascia stimulates and is connected with interoceptive and proprioceptive sensory receptors and brain pathways. Engaging with our fascia is an expression of agency: it is embedded in action and movement. It helps our bodies express their organic shape and size and essence and way of engaging with the world.

And in relating with our tissue as a sentient entity, as the subject of experience rather than its object, self-massage helps us claim our bodies as our own from the cellular level to an emotional and social one.

Hi Readers! Sometimes we can encounter a cool idea, but it’s not easy to put into practice. I’m teaching a practice class this Saturday focusing on Body Ownership, the last one of our summer series. We’ll be doing connective tissue work and exploring the themes in this article. If you’d like to register, you can do so directly below. If you can’t attend live, we make the recording available for seven days.

Summary:

Body ownership is the sense we have that our body belongs to us—it’s the me-ness of the body

The Rubber Hand Illusion is the primary mechanism that scientists have used to manipulate (and therefore learn about) body ownership in a laboratory setting

Body ownership also establishes where our boundaries, the boundaries of the bodily self, begin and end

We want a stable, yet also flexible, sense of boundaries (and body ownership)

Body ownership is a central focus of social justice, in areas from racial equity to gender justice to body sovereignty to disability justice

Connective tissue is a substrate for body ownership

Sources:

As one philosopher-scientist pointed out: de Vignemont, F. (2007). Habeas Corpus: The sense of ownership of one's own body. Mind & Language, 22(4), 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2007.00315.x

In the illusion, the researchers placed a rubber hand: Botvinick, M., & Cohen, J. (1998). Rubber hands ‘feel’ touch that eyes see. Nature, 391(6669), Article 6669. https://doi.org/10.1038/35784

and has spawned over 5,000 research papers: April 19, D. O., & 2020 7. (2020, April 19). Is There Really a “Rubber Hand” Illusion? Mind Matters. https://mindmatters.ai/2020/04/is-there-really-a-rubber-hand-illusion/

Importantly, the illusion does not occur when the rubber hand: Tsakiris, M. (2011). The sense of body ownership. In S. Gallagher (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the self (pp. 180–203). Oxford University Press.

The study established body ownership as a multisensory phenomenon: Tsakiris, M. (2017). The multisensory basis of the self: From body to identity to others [Formula: see text]. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (2006), 70(4), 597–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2016.1181768

There’s even been an analogue in mice: Mice Display Human-Like Sense of Body Awareness. (n.d.). The Scientist Magazine®. Retrieved August 6, 2023, from https://www.the-scientist.com/the-nutshell/mice-display-human-like-sense-of-body-awareness-32635

Including the fact that body temperature dropped: Moseley, G. L., Olthof, N., Venema, A., Don, S., Wijers, M., Gallace, A., & Spence, C. (2008). Psychologically induced cooling of a specific body part caused by the illusory ownership of an artificial counterpart. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(35), 13169–13173. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0803768105

Other studies found additional changes, including a release of histamines in the disowned hand and arm: Barnsley, N., McAuley, J. H., Mohan, R., Dey, A., Thomas, P., & Moseley, G. L. (2011). The rubber hand illusion increases histamine reactivity in the real arm. Current biology : CB, 21(23), R945–R946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.039

And studies show that when the rubber hand is threatened: Ehrsson, H. H., Wiech, K., Weiskopf, N., Dolan, R. J., & Passingham, R. E. (2007). Threatening a rubber hand that you feel is yours elicits a cortical anxiety response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(23), 9828–9833. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610011104

In fact, in some syndromes such as anorexia, people are more vulnerable to: Eshkevari, E., Rieger, E., Longo, M. R., Haggard, P., & Treasure, J. (2012). Increased plasticity of the bodily self in eating disorders. Psychological Medicine, 42(4), 819–828. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711002091

And as it turns out, people with a lower ability for interoception: Tsakiris, M., Tajadura-Jiménez, A., & Costantini, M. (2011). Just a heartbeat away from one's body: interoceptive sensitivity predicts malleability of body-representations. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 278(1717), 2470–2476. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.2547 See also: Fotopoulou, A., Jenkinson, P. M., Tsakiris, M., Haggard, P., Rudd, A., & Kopelman, M. D. (2011). Mirror-view reverses somatoparaphrenia: Dissociation between first- and third-person perspectives on body ownership. Neuropsychologia, 49(14), 3946–3955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.10.011. See also: Schroter, F. A., Siebertz, M., & Jansen, P. (2023). The Impact of a Short Body–Focused Meditation on Body Ownership and Interoceptive Abilities. Mindfulness, 14(1), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-02039-7

Footnotes:

In 2020, Lush et al. published a paper suggesting that a large proportion of Rubber Hand Illusion studies fall prey to the scientific problem of demand characteristics, meaning that the researchers; expectations are apparent to study participants, and therefore skew the results. Responses to this charge continue to fly back and forth across the scientific stratosphere. Personally, I don’t quite believe that demand characteristics can explain the physiological changes that occur with limb disownership (placebo aside), but it does seem clear that better controls can be used in future experiments.