Hey Readers! Some of you asked to be reminded about practice opportunities that come from my other newsletter devoted to Masterclasses and Body Love classes. (You can sign up for that here.)

We have a Body Love class coming up on Saturday, plus one each of the next three Saturdays. Read more and sign up HERE.

In last week’s column, I shared a bit about my lifelong relationship with ADHD and my recent discovery of an embodied tool that has proven more powerful than many at this moment in my life.

I hope that you feel liberated to make the tool “your own” and to tweak it in ways that work for you—and that you feel empowered to do this with virtually any tool you discover.

The “make it your own” thing isn’t merely a facile comment or a platitude: Tool tweaking, personalization, and creative experimentation are key tasks in adapting to and working with ADHD (and other forms of neurodivergence). These tasks are central elements of developing a responsiveness to your needs and of finding ways to make learning pleasurable for you. (Yes, pleasurable! Because learning inherently is rewarding and pleasurable, especially when the delivery system works for us; it’s just that our educational system environment may not be pleasurable, and its delivery systems may not mesh with us.)

Examples of the painful boxes that school systems tried to get me to fit into are etched in my memory as though they were yesterday.

Among them: High school science class. My 15-year-old self feels intensely agitated and under-stimulated. A mobile hangs just over my head; I’m driven to gently smack it with my hand so that it swings back and forth in the air. This makes my agitation feel better, so I do it again. Understandably, the science teacher orders me to stop; I’m compelled to hit the mobile several more times because it feels so good to be able to discharge even a small modicum of my agitation. Several minutes later, I’m in the principal’s office, sitting still again, trying to explain what compelled me to disobey. In Math class, which I love, I can focus for hours without a break. (The bummer about these kinds of interactions for kids like me is that we can start to equate their unpleasantness with the subject itself; I didn’t reclaim my love of science until ten years or so ago.) The school guidance counselor tells me it’s unlikely that I’ll get in to college—except, she qualifies, perhaps a state school. (Good thing I was a little oppositional, and that this made me even more determined to counter her recommendation. What would it be like, I often wonder, if more of us received help?)

Fast forward to graduate school. I’m sitting in neuroscience class, falling asleep despite pinching myself and drinking diet cokes to stay awake. Just prior to graduation, we go out to dinner with the teacher. He proposes a toast to me. He says he didn’t think I’d make it through school because of the sleeping issue. But to his surprise, I’d wake in the middle of class and ask an abstract, integrative question that somehow showed a high-level grasp of the material. I’d mull this over for years, trying to understand the elements: my sleeping in class, this capacity for abstract thought, and the missing of the foundational concepts underneath it.

That year, I’d discover one of the best tools that I still use to manage my ADHD and get work done: I’d go to the gym, get on the exercise bike with articles or pages of my writing, and read while biking. The exercise would funnel some of my excess agitation, leaving my mind to focus on my writing. (This is how I edited my entire first book, too—and how I’m editing chapters of the second.)

Just a few years later, summer. I’m studying for the psychology licensing exam. I stare out the windows of my apartment overlooking Lake Michigan. People walk, rollerblade, and boat. But I can’t do any of those things: Most of my time is spent managing my resistance to the test, and in not knowing how to prepare. The test consists of multiple-choice questions. Although I graduated from college with honors, I can’t understand the logic of multiple-choice. When I approach a question, it seems that many of the answers could be possible. I only start really studying in the last three weeks before the exam. I pass by a hair. The experience leaves me wondering: How does this test hope to determine whether someone with a doctoral degree is capable of being considered a practicing psychologist? (I think of one of my favorite mentors who did not pass this test three times, and what a great clinician, supervisor, and teacher he was.)

If you went to school before ADHD or individual learning plans were a thing, you may also have struggled mightily in the system. I never received help, even with a battery of psychological testing.

If you receive a late-life diagnosis or realization, this can also ignite a sense of grief for the time you’ve lost, or for the lack of understanding you’ve experienced. This is sometimes called ambiguous loss, a term coined by therapist Pauline Boss. The central idea is that this particular kind of loss carries little possibility for closure or resolution.

In ambiguous loss, you may experience someone’s physical presence, yet at the same time, their psychological absence. This happens, for example, in cases of dementia, mental illness, and sometimes in abuse. Alternatively, you might have someone who is physically absent but psychologically present. This occurs when someone is missing in action, or is deceased, or in other relationships that feel ongoing.

Ambiguous loss is real. Getting a late-life diagnosis or realization, or learning that your child might have this form of neurodivergence that society sees as flawed, can cause grief. There’s nothing wrong with you; it’s that we don’t embrace divergence well in modern society.

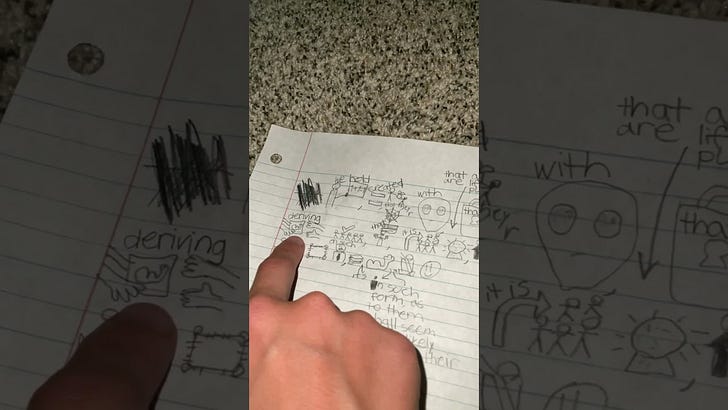

Today, I’m sharing with you an example of the resourcefulness and creativity that can accompany all divergent (read: creative) forms of learning when parents (and aunties!) collaborate to help a child “translate” an assignment into the style in which they learn best.

Let me set the scene: O.’s school required the kids to memorize the Declaration of Independence.

This assignment feels so odd to me, so divorced from notions of social inclusivity and equity. Consider the meaning of the document, which is basically, “We’re saying that we’re all created equal, but some of us (mainly white men) are more equal than others. Also, we’re going to use racist tropes right in the document, e.g. by referring to First Nations people as “merciless savages.”

Schools are still asking children to memorize (for what purpose?) a document with racism and violence embedded directly into it.

And then, of course, there’s the issue that auditory memorization doesn’t come easily to a massive group of humans. O.’s dad, my brother, suggested he make a visual map instead.

When O. showed me this map, I asked him to take me through it.

And that experience so blew me away that he suggested we record it together.

Recently, he gave me permission to include the map in June’s Masterclass on ADHD, which is going to be in our series of online Masterclasses in the next week or so. (I’ll put a little reminder in this column when it is, in case it’s helpful.)

Today, he said it was OK to share the visual mind map here on Substack. (I think he secretly might be kinda proud, but he’s 13 now and too cool to let it show in any obvious way.)

With that, I’m sharing this map in honor of the children in your life or in you.

This creation represents several of the many “superpowers” of ADHD people, which as you’ll see include resilience, creativity, resourcefulness, and a healthy dose of rebellion.

What I also see here—and these can exist side by side—is the misfitting of modern school systems: their square-peg-round-holeness, the cookie-cutter approach to learning, the need for kids to present in a uniform way. (This isn’t a matter of teacher quality; it’s the design of the modern Western school system.)

I also see something the brilliant Sebene Selassie speaks to. (check out her amazing Substack column here; it’s one of my favorites). Sometimes, a superpower of neurodivergence is the gift of being on the margins, and the perspective, and ability to reflect on the center, it offers us.

We hope it encourages you to understand yourself more every day, and to advocate for and experiment with the way you best learn and live in the world.

With love from O. and Auntie Bo

(Here they are with me in one of my favorite places in Boston Harbor; O. is the one on the left.)

Summary:

Tool tweaking, personalization, and creative experimentation are key tasks in adapting to and working with ADHD

Learning is pleasurable and rewarding when we find a way to do it that’s accessible for us

If you receive a late-life diagnosis or realization, this can also ignite a sense of grief known in professional circles as ambiguous loss

It takes time to learn what works for you, but that time is well worth it, as is finding ways to see your neurodivergence as a superpower

Kids rule!

Dear Bo, I've been longing for the time, space, and attention to savor your summer series. I love geeking out with you! This morning I took the Body Trust class from 7-22. I'm still reflecting on takeaways... the word which comes to mind now is spacious. Here's my question, which arose at the end: Something you said about the nervous system reminded me how many students are coming to me reporting "neuropathy." Google doesn't take body trust into account, and honestly I don't trust it. I'd love your take on neuropathy, whether a word, a sentence, an audio ramble...