In September of 2020, after a year on a waiting list, I left my gynecologist’s office, excitedly clutching a prescription for menopausal hormone therapy.

A full nine months would pass before I moved through my resistance to starting it.

I’m not an anomaly: Since 2002, menopausal hormone therapy has been surrounded by a cloud of fear and misinformation.

To understand what perpetuates this fear, we can look to the history of menopausal hormone research, the breach of protocol that stands out within it, and the far-reaching consequences that caused a full generation of women to suffer.

Menopause Science: The Early Years

In 1942, scientists developed a technique to extract urine from pregnant mares. The result was Premarin, the original estrogen tablets.

By the early 1990s, researchers had substantial evidence that taking supplemental hormones controlled the symptoms of menopause and preserved women’s health and well-being.

Studies showed that supplemental estrogen and progesterone reduced heart disease, lowered the incidence of osteoporosis and hip fractures, and decreased rates of colon cancer and dementia, all factors which compromise quality of life in postmenopausal women.

Even more remarkably, women who took estrogen had a longer life expectancy than those who did not.

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) became the standard of care for women in perimenopause and beyond.

In 1992, the American College of Physicians recommended menopausal hormone therapy for the prevention of heart disease. “All women, regardless of race, should consider preventive hormone therapy,” they stated. And furthermore, “women who have coronary heart disease or who are at increased risk for CHD are likely to benefit from hormone therapy.”

Cardiologist Bernadine Healy, the first female director of the National Institutes of Health, made the following statement in support of menopausal hormone therapy:

“The benefits of hormone replacement therapy on individual diseases or specific organs are impressive. But when the benefits are looked at in aggregate, they are compelling. The total health of a woman as she gets older is largely what determines her quality of life, what allows her to view the last half of her adult life as a blessing and a second prime.”

The Women’s Health Initiative Study

In 1998, the landmark Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study launched, supported by a staggering $625 million in funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under the National Institutes of Health.

The WHI study researchers randomly assigned 161,808 women to one of three clinical trials:

a hormone therapy trial which examined the risks and benefits of menopause hormones

a Calcium and Vitamin D trial

a Diet Modification arm, which examined the effects of low-fat diets on women’s health

Doctors, patients, and the media shared high hopes for the study, expecting it to confirm what the field already knew about the efficacy of menopausal hormone therapy.

But on July 9, 2002, in the span of an hour, the course of women’s healthcare changed irrevocably.

The Circumstances Leading Up to the Press Conference

In collaboration with the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), head researchers in the WHI study and the National Institutes of Health committed an unparalleled breach of scientific protocol and ethics.

They chose to hold a national press conference a full week before publishing their preliminary findings—a highly questionable practice. No one—colleagues, press, or public alike—had access to the study. They did not even give the study authors themselves the ability to give it a final review.

A mere 11 days before the press conference, the WHI’s 40 principal investigators gathered in Chicago, where they were told that the study had been terminated early.

When they received advance final proofs of the study report for JAMA, many of the investigators were shocked, angry, and concerned that the data had been misinterpreted. After spending almost a decade collaborating on the study, most investigators were denied input in either the decision to terminate the study or in its final and most critical paper. The investigators had no opportunity to ask critical questions that would have clarified important omissions in the data and its interpretation.

For more than a week after the press conference, the WHI investigators and the National Institutes of Health refused to share the raw data with doctors—except, according to reports, some with links to prestigious cancer councils. Most knew nothing of the paper. They also kept the data from outside companies or those who manufactured the study drugs. This enabled them to protect their monopoly over the data and their prerogative to publish follow-up data on their own terms. (I learned this from an article on the study aptly titled, “How not to release data from your RCT.”)

In other words, they privileged the agendas of industry, government, and politics, and marginalized science and patient care.

The Ill-Fated Press Conference That Compromised Menopause Care

On July 9, 2002, Jacques Rossouw, Chief Investigator at the National Institutes of Health began the press conference with an acknowledgment that choosing whether to take postmenopausal hormone therapy is one of the most important health decisions that women face.

In a remarkable display of hubris, he followed that statement by saying that NIH was aiming for “high impact with the goal to shake up the medical establishment and change their thinking about hormones.”

To say that they achieved their aims would be a gross understatement.

At the press conference, they announced that the combined estrogen/progesterone hormone trial had been terminated early due to “increased breast cancer risk.”

They informed the press and the public that menopause hormones increased a woman’s risk of heart attack by a full 29 percent.

In the Wake of the WHI Press Conference

The news traveled like a virus. Countless media outlets replicated its message, infecting doctors and patients alike with fear.

A headline on the front page of the New York Times trumpeted, “Hormone Replacement Study a Shock to the Medical System.”

The front page of the BBC News screamed, “HRT linked to breast cancer.”

The Sydney Morning Herald featured a banner headline reading “Hormone Alert for Cancer.” The article announced that “up to 600,000 Australian women had been advised to stop taking HRT” because new research revealed that it increases their risk of cancer.

Several doctors, many of them women, immediately spotted the flaws in the study.

Dr. Scott Gottleib, former commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), described the event as a “carefully orchestrated PR blitz.”

Gottleib noted that federal researchers refused to share the results, even with outside academics or with the drug manufacturers. This, he said, allowed the researchers to carefully guard their control over the data—and with it, the capacity to publish follow-up findings.

Had the data been more widely shared, Gottleib noted, key analyses that debunked its initial conclusions would have been publicly disseminated much sooner.

Professor David Purdie, from the Centre for Metabolic Disease at Hull Royal Infirmary, urged women not to be frightened by the study. Speaking to BBC News Online, he said:

"No British women should stop taking HRT on the basis of these results, and if she is at all concerned, she should discuss it with her doctor. It is a time for cool heads on this side of the Atlantic."

He said the risks of breast cancer, heart disease and stroke were very low.

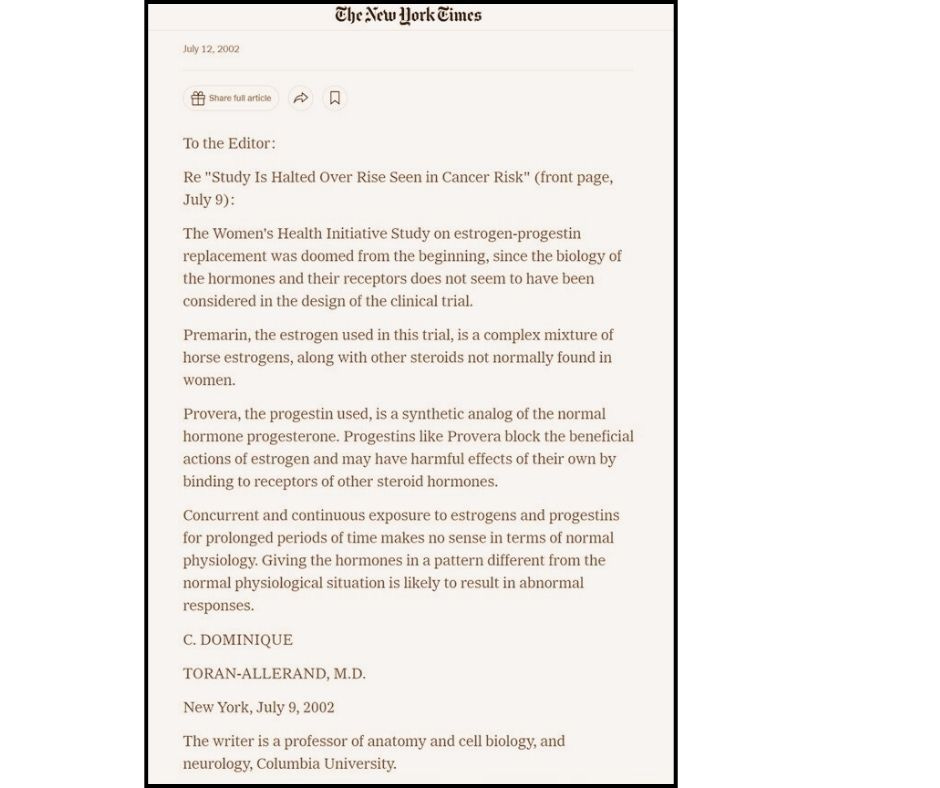

Other doctors wrote in to numerous media sources. Consider the following opinion letter in the New York Times:

C. Dominique Toan-Allerand, M.D., a professor of anatomy, cell biology, and neurology at Columbia University, wrote to the New York Times. She stated:

To the Editor:

Re: “Study is Halted Over Rise Seen in Cancer Risk (front page, July 9):

The Women’s Health Initiative Study on estrogen-progestin replacement was doomed from the beginning, since the biology of the hormones and their receptors does not seem to have been considered in the design of the clinical trial.

Premarin, the estrogen used in this trial, is a complex mixture of horse estrogens, along with other steroids not normally found in women.

Provera, the progestin used, is a synthetic analog of the normal hormone progesterone. Progestins like Provera block the beneficial actions of estrogen and may have harmful effects of their own by binding to receptors of other steroid hormones.

Concurrent and continuous exposure to estrogens and progestins for prolonged periods of time makes no sense in terms of normal physiology. Giving the hormones in a pattern different from the normal physiological situation is likely to result in abnormal responses.

But the damage was done. Widespread panic ensued among women about the significant public health implications of MHT.

The final message was electrifying: Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) was dangerous and increased the risk of both heart disease and breast cancer and heart disease, the number one and number three causes of death for U.S. women, respectively.

What the Press Conference and Published Study Got Wrong

At the WHI press conference, Jacques Rossouw told the media that the adverse effects of Menopausal Hormone Therapy applied to all women irrespective of age, ethnicity, or disease status, a grievous misinterpretation of the study data.

The study data were not released in age cohorts, a serious scientific error. This prevented interpretation of the data with respect to the age groups of the women, a key factor in the interpretation of the study.

The average age of participants in the study was 63 and the participants were 79.

This meant that the average participant was postmenopausal; in fact, many were a full 20 years past menopause when the WHI study began. This meant that not only were they taking hormones well beyond the accepted window for intervention, but that most didn’t have symptoms of menopause, which also led to the investigators’ assertion that menopausal hormone therapy did not improve symptoms.

According to doctors familiar with the study design, the WHI study both actively recruited older women, and also discouraged women with moderate to severe symptoms from participating in the study. (Women with moderate to severe symptoms of menopause would generally be younger than the average study participant, and would benefit more from hormone therapy.)

Subsequent analyses revealed that both a woman’s age and the timing of hormone use dramatically altered the risks and benefits, just as the researchers hypothesized at the study’s outset.

A closer examination of the data revealed that women in their 50s who took a combination of estrogen and progestin or estrogen alone had a lower risk of dying than women who didn’t take hormones.

What’s more, women in their 50s who regularly used estrogen alone had a lower risk for severe coronary artery calcium (a risk factor for heart attack), a reduced risk of coronary heart disease and breast cancer, and a reduced risk of all-cause mortality.

In July of 2007, five years after the initial release of the study, the WHI trial revised its findings on cardiovascular risk.

The New England Journal of Medicine reported that women aged 50-59 in the WHI study who regularly used estrogen alone showed a 60 percent drop in risk for severe coronary artery calcium, a key risk factor for heart attacks.

And a study co-authored by none other than Jacques Rossouw, and published in JAMA, acknowledged that women who initiated hormone therapy closer to menopause tended to have a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease compared with those who did so later than menopause.

The Fallout from The Study’s Publicity

Despite countless later findings indicating HRT’s benefits, the WHI researchers’ dramatic presentation of the WHI's results contributed to a misunderstanding of the therapy's safety and benefits.

The media’s alarmist coverage added to the lasting confusion and fear about HRT.

The consequences proved devastating for menopausal women, and for the care of the menopausal care in midlife and beyond.

Virtually overnight, more than 80% of prescriptions for menopausal hormone therapy were discontinued.

The negative press from the study had an even larger impact on menopausal hormone therapy initiation, with the largest drop occurring in women who had doctors’ appointments after the press conference in July of 2002.

In the three years after publication of the WHI study, the incidence of fractures among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women increased significantly.

In women as young as 40 and up to the age of 69, fractures rose from 919,389 in 2000 to a whopping 2,872,372 in 2005—a bump of more than 300%. This increase occurred among radius and ulna, vertebra, ribs, hip, pelvis, and, sadly, in multiple pathologic fractures. This alarming trend directly followed a decline in the use of hormone therapy, concurrent with an increase in the use of other bone-modifying agents.

Even more disturbing, a study published by the American Journal of Public Health in 2013 estimated that between 18,601 and 91,000 postmenopausal women in the U.S. died prematurely due to avoidance of estrogen therapy.

In their conclusion, the study authors warned,

“ET in younger postmenopausal women is associated with a decisive reduction in all-cause mortality, but estrogen use in this population is low and continuing to fall.”

The Chilling Effects of the WHI Debacle on Medical Menopause Education

To my mind, an additional way that the WHI study rollout shaped the future of menopause care is to minimize its importance not only with patients, but in the training of the medical professionals who provide that care.

In medicine, an inadequate understanding of menopause—and its impact on multiple intersecting systems in the mind, brain, and body—remains a critical issue in women’s health.

Medical school offers little to no formal training in menopause. A survey study of medical students found that 83.8 percent of respondents believed that their program required more menopausal education resources. A full 100 percent of medical school programs reported less than six menopause lectures per year, while 71 percent reported less than two lectures.

The Menopause Society has called for an easily accessible, standardized menopause curriculum across multiple residency programs, including obstetrics and gynecology, internal medicine, and family medicine, where many women present with symptoms seemingly unrelated to menopause.

The Menopause Society’s aim is that “all women have access to competent medical care.” (In my opinion, “competent” should be the baseline of care, and high-quality care the goal.)

And lack of formal education in menopause, compounded by a glaring gender bias in scientific research, has perpetuated an inadequate understanding of the way menopause impacts women and who it impacts differently.

The lack of appropriate diagnosis and care doesn’t affect all women equally.

The Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) study in the U.S. was a multiracial, multiethnic study that ran from 1996-2003 and included more than 3,000 women as they entered menopause. The study authors examined median duration of hot flashes and other vasomotor symptoms (VMS) such as night sweats. The researchers found that Black women had the longest duration of vasomotor symptoms (which, when left untreated, can impact health in myriad ways, including bone desity).

Black and Latine women enter perimenopause sooner than the median age, often in their 30’s. Their symptoms begin earlier, are often more severe, and tend to be misdiagnosed more often by doctors.

Despite a greater severity of vasomotor and other symptoms, Black women have had the lowest prevalence of MHT use. This is true both before the WHI study—from 1999 to 2000—as well as recently, from 2017 to 2020. They also had the greatest decline in menopausal hormone therapy in the aftermath of the WHI study.

Strikingly, Black women are twice as likely as white women to have their uterus (hysterectomy) or ovaries (oophorectomy) removed for benign conditions (at a rate of a whopping 30 percent vs. 15 percent).

Socioeconomic factors also influence hormone therapy use. Higher family income and insurance coverage correlate with increased MHT use And among Black and Latine women, educational attainment meant that they were more likely to receive MHT—while this was not the case for white women. These findings underscore the persistent racial and class disparities in menopause care, corroborating previous literature.

The Dark Side of the WHI Study

The media plays a key role in the dissemination of scientific findings—sometimes, to public detriment.

A paper published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 1998, just four years before the WHI press release, found that 84 percent of newspaper articles on health and science topics used articles mentioned in press releases as primary sources.

And in June of 2002, JAMA published a paper entitled, “Press Releases.” In it, they reported that in a survey of nine medical journals that included 127 press releases, study limitations were rarely mentioned, industry (or government) funding was not mentioned, and data were often presented using formats that could exaggerate the perceived importance of findings.

Yet one month after the paper, the same journal (JAMA) engineered the Women’s Health Initiative press conference, and declined to discuss either the study limitations or its sources.

For more than a decade, debate, discussion and disagreement ensued in research and medicine. Serious allegations began to surface against some of the investigators in the Women’s Health Initiative. These allegations have implied that the dissemination of the study results violated guidelines on how trial data should be presented.

In 2007, five years after the WHI study was terminated, critics began to speak out more publicly, including some of the WHI’s own investigators.

Robert D. Langer, a former principal investigator for the WHI’s clinical center at the University of California, was among those who protested at the time of the study’s release, and in the years that followed it.

“Had the initial report been written by a broader group, as almost all of our later papers have been, it would have been framed differently,” Langer said in an interview in 2007. He expressed concern that the interpretation of the WHI unnecessarily scared a generation of women away from menopausal hormone therapy.

In 2016, The New England Journal of Medicine published a commentary in which two key WHI investigators noted that ‘the WHI results are being used inappropriately in making decisions about treating women in their 40s and 50s who have distressing vasomotor symptoms.” Many of the original claims were misunderstood.

And in a 2017 paper titled “The evidence base for HRT: what can we believe?” Robert Langer raised concerns about the due process involving the data evaluation, writing, author approval, and publication of the WHI paper. Langer argued that a cohort of the study’s investigators “hijacked” the data. He accused the small group of erroneously reporting that the study was cut short because of higher risks of women developing breast cancer and heart attacks from the hormonal treatment.

Rodney Baber, professor and editor in chief of the Climacteric, the journal that published Langer’s article, wrote an accompanying editorial. He stated, “This new study raises questions about due process surrounding the data evaluation, writing, author approval and publication of the original WHI paper.” Baber’s piece, I’ll add, had the apt title, “What is scientific truth?”

Some wonder why these researchers waited so long to come forward.

Jacques Rossouw, the star of the WHI press conference, seems to have come through the fire unscathed.

In 2006, Time Magazine named Rossouw one of the 100 Most Influential People. His generous profile was penned by American writer and political activist Barbara Ehrenreich.

Ehrenreich lauded the key players in the WHI study, including the cardiologist Bernadine Healy. Of Rossouw, she enthused:

The standing ovation goes to a man, Jacques Rossouw, 63, the South African-born physician who heads the WHI. A modest fellow, he considers himself "gender impaired," but maybe it took a man to make it happen — "a real insider," as Cindy Pearson, director of the National Women's Health Network, puts it. "He's passionate and committed, articulate. It may have been 'women's work,' but he was the man for the job."

The man for the job? If we’re talking about the hatchet job that demolished a generation of menopausal care, I’d agree wholeheartedly.

The North American Menopause Society’s 2022 Statement on MHT

In 2022, the North American Menopause Society issued a new statement on menopausal hormone therapy, powered by an advisory panel of expert clinicians in the fields of women’s health and menopause care. These experts reviewed the previous statement from 2017, evaluated new research, and reviewed evidence.

The new statement reads,

Hormone therapy remains the most effective treatment for vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the genitourinary syndrome of menopause and has been shown to prevent bone loss and fracture. The risks of hormone therapy differ depending on type, dose, duration of use, route of administration, timing of initiation, and whether a progestogen is used. Treatment should be individualized using the best available evidence to maximize benefits and minimize risks, with periodic reevaluation of the benefits and risks of continuing therapy.

For women aged younger than 60 years or who are within 10 years of menopause onset and have no contraindications, the benefit-risk ratio is favorable for treatment of bothersome VMS and prevention of bone loss. For women who initiate hormone therapy more than 10 years from menopause onset or who are aged older than 60 years, the benefit-risk ratio appears less favorable because of the greater absolute risks of coronary heart disease, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and dementia.

_________________________________________

My heart goes out to the generation of women across the world left behind by the WHI researchers’ grievous miscarriage of ethics.

More than 47 million people globally and 2 million in the U.S. enter menopause each year, typically between the ages of 45 and 55—and by the year 2030, that number is projected to reach 1.2 billion.

The numbers for perimenopause are even higher. Most people enter this in-between stage between the ages of 35 and 45.

As of 2020, research shows, more than half of all women globally were unaware of the symptoms of perimenopause, and felt surprised and unprepared for it when it began.

My hope is that not one more person will have their symptoms of menopause overlooked, and that each human will have the support and knowledge they need to navigate this transition.

The failure of the WHI researchers to publicly and unequivocally walk back their statements. (One of the primary researchers, a long-respected member of NAMS who I heard on a podcast early this year, remains defiant, and defiantly conservative on menopausal hormone therapy.)

And in the yoga and wellness worlds, the insistence (prematurely, in my opinion) on “menopausal empowerment” and doing menopause “the natural way” rings like an anthem in my ears. What, after all, is more natural than bioidentical estrogen and progesterone?

These are the catalysts that drive me to write, teach, and speak about emerging research and therapeutics in menopause care.

I hope that anyone reading or listening spreads the word to those they love.

Sources:

Studies showed that supplemental estrogen reduced the incidence of heart disease: Lobo, R. A., Pickar, J. H., Stevenson, J. C., Mack, W. J., & Hodis, H. N. (2016). Back to the future: Hormone replacement therapy as part of a prevention strategy for women at the onset of menopause. Atherosclerosis, 254, 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.10.005

Even more dramatically, women taking estrogen had a longer life expectancy: Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE, Joffe M, Rosner B, Fuchs C, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 19;336(25):1769-75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706193362501. PMID: 9187066 . See also: Grady D, Rubin SM, Petitti DB, Fox CS, Black D, Ettinger B, Ernster VL, Cummings SR. Hormone therapy to prevent disease and prolong life in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 1992 Dec 15;117(12):1016-37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-12-1016. PMID: 1443971.

Their statement suggested that “all women, regardless of race, should consider preventive hormone therapy: Counseling Postmenopausal Women About Preventive Hormone Therapy*—- 1996—Journal of the American Geriatrics Society—Wiley Online Library. (n.d.). Retrieved October 10, 2024, from https://agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02952.x

Cardiologist Bernadine Healy, the first female director of the National Institutes of Health, said of MHT: Tavris, C., & Bluming, A. (2018). Estrogen Matters: Why Taking Hormones in Menopause Can Improve Women’s Well-Being and Lengthen Their Lives -- Without Raising the Risk of Breast Cancer (2nd edition). Little, Brown Spark.

In 1991, the landmark Women’s Health Initiative study launched: Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) | NHLBI, NIH. (n.d.). Retrieved October 10, 2024, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/science/womens-health-initiative-whi

They chose to hold a national press conference a full week before publishing their preliminary: Press Conference Comments—Dr. Rossouw. (n.d.). Retrieved October 9, 2024, from https://sp.whi.org/participants/findings/Pages/ht_eplusp_rossouw.aspx

A mere eleven days before the press conference, the WHI’s 40 principal investigators gathered in Chicago, where they were told: How NIH Misread Hormone Study in 2002—WSJ. (n.d.). Retrieved October 28, 2024, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118394176612760522

Medical professionals had no access to the unpublished data for more than a week after the press conference: Staples, R. (2017, July 27). Hormone alert for cancer: How not to release data from your RCT. O&G Magazine. https://www.ogmagazine.org.au/18/1-18/hormone-alert-cancer-not-release-data-rct/

Jacques Rossouw, Chief Investigator at the National Institutes of Health began with an acknowledgment that choosing whether to take postmenopausal hormone therapy: Press Conference Comments—Dr. Rossouw. (n.d.). Retrieved October 9, 2024, from https://sp.whi.org/participants/findings/Pages/ht_eplusp_rossouw.aspx

And in a remarkable display of hubris, he followed that statement by saying that NIH was aiming for “high impact with the goal to shake up the medical establishment: Staples, R. (2017, July 27). Hormone alert for cancer: How not to release data from your RCT. O&G Magazine. https://www.ogmagazine.org.au/18/1-18/hormone-alert-cancer-not-release-data-rct/

They informed the press and public that menopause hormones increased a woman’s risk of heart attack by a full: How NIH Misread Hormone Study in 2002—WSJ. (n.d.). Retrieved October 28, 2024, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118394176612760522

A headline on the front page of the New York Times trumpeted: Kolata, G. (2002, July 9). Study Is Halted Over Rise Seen In Cancer Risk. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/09/us/study-is-halted-over-rise-seen-in-cancer-risk.html See also: Petersen, G. K. W. M. (2002, July 10). Hormone Replacement Study A Shock to the Medical System. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/10/us/hormone-replacement-study-a-shock-to-the-medical-system.html

The BBC News screamed, “HRT linked to breast: HRT linked to breast cancer. (2002, July 10). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/2117501.stm

The Sydney Morning Herald featured a banner headline reading: Alarm over HRT cancer risk. (2002, July 10). The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/alarm-over-hrt-cancer-risk-20020710-gdffus.html

Dr. Scott Gottleib, former commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration: The War on (Expensive) Drugs. (n.d.). American Enterprise Institute - AEI. Retrieved October 27, 2024, from https://www.aei.org/articles/the-war-on-expensive-drugs/

Had the data been more widely shared, Gottleib noted, key analyses that debunked: The War on (Expensive) Drugs. (n.d.). American Enterprise Institute - AEI. Retrieved October 27, 2024, from https://www.aei.org/articles/the-war-on-expensive-drugs/

Professor David Purdie, from the Centre for Metabolic Disease at Hull Royal Infirmary, urged women not: HRT linked to breast cancer. (2002, July 10). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/2117501.stm

Several doctors, many of them women, spoke out about the flaws: Opinion | A Cloud Over Hormone Therapy. (2002, July 12). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/12/opinion/a-cloud-over-hormone-therapy.html

At the WHI press conference, Rossouw told the media assembled at the press conference that the adverse effects: Press Conference Comments—Dr. Rossouw. (n.d.). Retrieved October 9, 2024, from https://sp.whi.org/participants/findings/Pages/ht_eplusp_rossouw.aspx See also: Staples, R. (2017, July 27). Hormone alert for cancer: How not to release data from your RCT. O&G Magazine. https://www.ogmagazine.org.au/18/1-18/hormone-alert-cancer-not-release-data-rct/

The average age of women in the study was 63: How NIH Misread Hormone Study in 2002—WSJ. (n.d.). Retrieved October 28, 2024, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118394176612760522

Furthermore, according to doctors familiar with the study design, the WHI study actively discouraged women: Bluming, A. and Tavris, C. Estrogen matters. Why taking hormones in menopause can improve women’s well-being and lengthen their lives: Without raising the risk of breast cancer. Little Brown Spark: New York, 2018.

A closer examination of the data revealed that women in their 50s who took a combination of estrogen and progestin or estrogen alone had a lower risk of dying: Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. (2002). Risks and Benefits of Estrogen Plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal WomenPrincipal Results From the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA, 288(3), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.3.321

What’s more, women in their 50s who regularly used estrogen alone had a lower risk for: Manson, J. E., Allison, M. A., Rossouw, J. E., Carr, J. J., Langer, R. D., Hsia, J., Kuller, L. H., Cochrane, B. B., Hunt, J. R., Ludlam, S. E., Pettinger, M. B., Gass, M., Margolis, K. L., Nathan, L., Ockene, J. K., Prentice, R. L., Robbins, J., & Stefanick, M. L. (2007). Estrogen Therapy and Coronary-Artery Calcification. New England Journal of Medicine, 356(25), 2591–2602. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa071513

The New England Journal of Medicine reported that women aged 50-59 in the WHI study who regularly used estrogen alone: Manson, J. E., Allison, M. A., Rossouw, J. E., Carr, J. J., Langer, R. D., Hsia, J., Kuller, L. H., Cochrane, B. B., Hunt, J. R., Ludlam, S. E., Pettinger, M. B., Gass, M., Margolis, K. L., Nathan, L., Ockene, J. K., Prentice, R. L., Robbins, J., & Stefanick, M. L. (2007). Estrogen Therapy and Coronary-Artery Calcification. New England Journal of Medicine, 356(25), 2591–2602. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa071513

And a study co-authored by none other than Jacques Rossouw and published in JAMA: Rossouw, J. E., Prentice, R. L., Manson, J. E., Wu, L., Barad, D., Barnabei, V. M., Ko, M., LaCroix, A. Z., Margolis, K. L., & Stefanick, M. L. (2007). Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease by Age and Years Since Menopause. JAMA, 297(13), 1465–1477. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.13.1465

The dramatic quality of the announcement set the tone for the initial news reports:

S, B. (2012). Shock, terror and controversy: How the media reacted to the Women’s Health Initiative. Climacteric : The Journal of the International Menopause Society, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2012.660048

The negative press from the study had an even larger impact on menopausal hormone therapy initiation: Crawford SL, Crandall CJ, Derby CA, El Khoudary SR, Waetjen LE, Fischer M, Joffe H. Menopausal hormone therapy trends before versus after 2002: impact of the Women's Health Initiative Study Results. Menopause. 2018 Dec 21;26(6):588-597. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001282. PMID: 30586004; PMCID: PMC6538484.

In the three years after publication of the WHI study, the incidence of fractures among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: Islam, S., Liu, Q., Chines, A., & Helzner, E. (2009). Trend in incidence of osteoporosis-related fractures among 40- to 69-year-old women: analysis of a large insurance claims database, 2000-2005. Menopause (New York, N.Y.), 16(1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31817b816e

This increase occurred among radius and ulna, vertebra, ribs, hip, pelvis: Islam, S., Liu, Q., Chines, A., & Helzner, E. (2009). Trend in incidence of osteoporosis-related fractures among 40- to 69-year-old women: analysis of a large insurance claims database, 2000-2005. Menopause (New York, N.Y.), 16(1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e31817b816e

Even more disturbing, a study published by the American Journal of Public Health in 2013: Sarrel, P. M., Njike, V. Y., Vinante, V., & Katz, D. L. (2013). The mortality toll of estrogen avoidance: an analysis of excess deaths among hysterectomized women aged 50 to 59 years. American journal of public health, 103(9), 1583–1588. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301295

A survey study of medical students found that 83.8 percent of respondents: Allen, J. T., Laks, S., Zahler-Miller, C., Rungruang, B. J., Braun, K., Goldstein, S. R., & Schnatz, P. F. (2023). Needs assessment of menopause education in United States obstetrics and gynecology residency training programs. Menopause, 30(10), 1002. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002234

The Menopause Society called for an easily accessible, standardized menopause curriculum: Stephanie Faubion, medical director for The Menopause Society.

Society, T. M. (n.d.). New survey confirms need for more menopause education in residency programs. Retrieved October 10, 2024, from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2023-08-survey-menopause-residency.html

They found that Black women had the longest duration of vasomotor symptoms: Duration of Menopausal Vasomotor Symptoms Over the Menopause Transition—PMC. (n.d.). Retrieved September 22, 2024, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4433164/

Their symptoms begin earlier, are often more severe, and tend to be misdiagnosed: Green, R., & Santoro, N. (2009). Menopausal Symptoms and Ethnicity: The Study of Women’s Health across the Nation. Women’s Health, 5(2), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.2217/17455057.5.2.127

Despite a greater severity of vasomotor and other symptoms, Black women have had the lowest prevalence of MHT: Iyer, T. K., & Manson, J. E. (2024). Recent Trends in Menopausal Hormone Therapy Use in the US: Insights, Disparities, and Implications for Practice. JAMA Health Forum, 5(9), e243135. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.3135 See also: Yang, L., & Toriola, A. T. (2024). Menopausal Hormone Therapy Use Among Postmenopausal Women. JAMA Health Forum, 5(9), e243128. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2024.3128

Black women are twice as likely as white women to have their uterus removed: Powell, L. H., Meyer, P., Weiss, G., Matthews, K. A., Santoro, N., Randolph, J. F., Schocken, M., Skurnick, J., Ory, M. G., & Sutton-Tyrrell, K. (2005). Ethnic differences in past hysterectomy for benign conditions. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 15(4), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2005.05.002

Socioeconomic factors also influence hormone therapy use: Blanken, A., Gibson, C. J., Li, Y., Huang, A. J., Byers, A. L., Maguen, S., Inslicht, S., & Seal, K. (2022). Racial/ethnic disparities in the diagnosis and management of menopause symptoms among midlife women veterans. Menopause, 29(7), 877. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001978

These findings underscore the persistent racial and class disparities in menopause care: Blanken, A., Gibson, C. J., Li, Y., Huang, A. J., Byers, A. L., Maguen, S., Inslicht, S., & Seal, K. (2022). Racial/ethnic disparities in the diagnosis and management of menopause symptoms among midlife women veterans. Menopause, 29(7), 877. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001978

A paper published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 1998: de Semir, V., Ribas, C., & Revuelta, G. (1998). Press releases of science journal articles and subsequent newspaper stories on the same topic. JAMA, 280(3), 294–295. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.3.294

And in June 2002, JAMA published a paper entitled, “Press Releases.”: Woloshin, S., & Schwartz, L. M. (2002). Press releases: translating research into news. JAMA, 287(21), 2856–2858. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.21.2856

Serious allegations against some of the investigators in the Women’s Health Initiative imply that: Kegel, M. (2017, March 24). Breast Cancer-related Clinical Trial Controversy Resurfaces. Breast Cancer News. https://breastcancer-news.com/2017/03/24/controversy-over-breast-cancer-risk-of-hormone-replacement-therapy-resurfaces/

“Had the initial report been written by a broader group, as almost all of our later papers have been: How NIH Misread Hormone Study in 2002—WSJ. (n.d.). Retrieved October 26, 2024, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118394176612760522

In 2016, The New England Journal of Medicine published a commentary in which two key WHI investigators: Manson, J. E., & Kaunitz, A. M. (2016). Menopause Management—Getting Clinical Care Back on Track. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(9), 803–806. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1514242

In a 2017 article entitled, “The evidence base for HRT: what can we believe?,” Professor Robert D. Langer argued that a cohort: Langer, R. D. (2017). The evidence base for HRT: What can we believe? Climacteric: The Journal of the International Menopause Society, 20(2), 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1280251

Rodney Baber, professor and editor in chief of the Climacteric, the journal that published Langer’s article: Baber, R. (2017). What is scientific truth? Climacteric, 20(2), 83–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1295220

In 2006, Rossouw was named to the Time 100 Most Influential People: Ehrenreich, B. (2006, May 8). The 2006 TIME 100—TIME. Time. https://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0%2c28804%2c1975813_1975844_1976459%2c00.html

In 2022, the North American Menopause Society issued a new statement on menopausal hormone therapy: The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. (2022). Menopause, 29(7), 767. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

Each year, more than 47 million people globally: Menopausal women will make up the biggest U.S. demographic—So why is medicine still ignoring them? - MarketWatch. (n.d.). Retrieved October 9, 2024, from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/menopausal-women-will-make-up-the-biggest-u-s-demographic-so-why-is-medicine-still-ignoring-them-055d72eb

Is progesterone alone helpful? Historically I had problems with taking estrogen in the form of birth control in the early 90s, getting mood swings (I understand that the % of estrogen was much higher then in BC?). A friend who is in the throes of perimenopause tried estrogen and progesterone together and was an emotional wreck, with symptoms of depression. Any feedback you could give would be most helpful. Thanks.