When Emotional Contagion Cuts Deep

The little-known scourge of projective identification

Have you ever come sailing through the front door after an amazing day, filled with exuberance, only to find yourself minutes later, seething with rage toward your partner? Or taught an artful workshop and stayed after to answer questions, only to be flooded by the conviction that your teaching skills (and possibly you) are in fact absolute shit? Or had a seemingly harmless encounter at a party that caused your belly to roil with adrenaline and your heart to beat in sudden alarm?

These experiences have different manifestations, yet share a common mechanism.

Last week’s column outlined sensory and emotional contagion, in which we “catch” others’ sensations and emotions the way as we would a cold or flu.

This week, I’d like to explore a hidden dynamic in extreme cases of emotional contagion. By this, I mean that sometimes we experience “garden variety” emotional contagion. But sometimes, it’s more primal and all-consuming.

I learned about the more insidious kind in graduate school, but nothing could have prepared me for its real-life experience. Knowing that this dynamic exists, how it manifests, and what you can do to address it can give your boundaries and well-being a serious upgrade.

Defense Mechanisms + Empathic Distress

We all have an arsenal of psychological defense mechanisms, strategies that the conscious mind deploys to protect us from discomfort. (This is a key point to remember, and one we’ll return to in just a bit.) Why, exactly, does the mind do that?

Humans have a universal need to belong, to be part of a larger social group. From a very young age, we receive numerous messages about social taboos, prohibitions against expressing parts of us that threaten our social bonds. This starts with caregivers and how they feel about these parts of us—but soon it expands to society as a whole.

Some taboos are reasonable, like refraining from actions that are criminal, cruel, or unwise. Some are unreasonable, and prohibit expressions of our innerness that challenge social norms. The need to belong plays a role in the suppression of myriad experiences, from sexual desire to sudden rage, from mystery inflammation to unexplained pain, from envy to gender to sexual orientation.

Some aspects of sensation, emotion, thought, and experience remain accessible to the conscious mind. But to protect the vulnerable parts of ourselves, we send some into hiding. When something brings them close to the surface, we rely on a range of defenses mechanisms to keep them under wraps.

The field of psychology distinguishes between higher-functioning or adaptive defenses and lower-functioning, primitive, or maladaptive ones. At the higher-functioning level, the mind is partially aware of these defenses; at the lower-functioning level, less so.

A more adaptive defense, for instance, is suppression. When you experience a desire that would have negative consequences (say, attraction to someone else’s partner), you may consciously put it to the side and decline to express it. Or perhaps you feel comfortable with an emotion like sadness, but anger feels threatening, so you suppress it.

On a less adaptive and more neurotic level, you might find passive aggression. For example, rather than tell someone directly that you’re upset (and risk their anger or rejection), you might give them the silent treatment instead. It’s passive because you don’t express the feelings, but aggressive in that your anger comes across just the same (and whoa, does it ever).

We all use psychological defenses; they’re part of the human experience. They help maintain a stable identity and ensure a measure of comfort. But when we deploy them unconsciously, they are forms of disembodiment. Left unchecked, they often result in harm to ourselves and to others.

The Dark Art of Projective Identification

Most of us are familiar with projection, a fairly immature defense. Projection refers to the transfer of positive or negative qualities that we can’t acknowledge onto someone else, like a therapist, partner, boss, or child. We might see a mentor as brilliant, all-wise, unparalleled in every way but deny those qualities in ourselves. Or view a child or partner as angry or oppositional, and be blind to our own defiance—which, to others, is majorly obvious.

Yet projection is a walk in the park compared with its car more maladaptive counterpart, projective identification.

Here’s how projective identification works. Someone takes the sensations, emotions, and experiences so overwhelming as to potentially fragment them, and forces them not onto us but into us. These are not everyday emotions like anger or sadness but primal ones: think full-on murderous rage, shame, self-hatred, or envy.

Projective identification is an intrapsychic (within the psyche) defense that becomes interpersonal (between two or more people). It’s like painting your insides onto someone else’s inner canvas.

Projective identification carries no warning signal or alarm; we simply experience its flood of primal feelings and sensations as though they are part of us. Projective identification is usually deeply unconscious for the giver and receiver alike.

Projective identification can have multiple purposes:

When it occurs with people we know, like a partner or therapist, projective identification can be a means of relating

It can be a mode of learning, in which someone studies the way we metabolize and transform difficult experiences so that they can eventually do the same

It can function as a way for people to rid themselves of intolerable experiences

In some intimate relationships, particularly abusive ones, it can be a means of coercion, a way to control the target’s mind and body

Nonetheless, forcing unconscious and unprocessed parts of oneself into someone else is a significant boundary violation. And when we don’t know it’s happening, it’s hard to strip the paint from our inner walls—or even, to recognize the pattern as not of our own design.

Spotting Projective Identification

If projective identification happens with a loved one—a parent, partner, or child—you may not know it came from them. The sensations and emotions you experience may have felt like part of you for decades.

Here are some signs to help you recognize when it’s in play:

The sensations and emotions you feel are often sudden, intense, feel foreign, and occur without warning

There’s a pervasiveness to the experience; it permeates your entire being

You often feel a sense of invasion

You may feel a nervous system alarm, a sense of agitation

You can have wild surges of emotional dysregulation

The aftermath can linger like the effects of a toxin

Your self-care can plummet

You might imagine a correlation: that what a “projector” sends and what the target receives is always the same—say, rage projected and received. But that’s not always the case.

Nearly ten years ago, I found myself participating in a group meditation led by a somatic mindfulness teacher. She was a gentle soul, soft spoken, with a smile always at the ready. But as she led us through the meditation, a searing pain began to build in my body, starting in my spine. It was at first mildly disruptive, if unusual. But as her dulcet tones reached the 20-minute mark, the pain grew so severe that I nearly fell off the puckered navy meditation cushion. With each passing moment, I had to resist the impulse to jump up and let forth an urgent, ululating shout. After it ended, I stumbled to the dining room and collapsed into a chair next to a colleague and a person from his lab. He asked us how we’d found the meditation. I prepared something polite, only to find that the pain had undone my restraint and I could not dissemble; the story came tumbling out. To my surprise, my colleague asked if I’d heard of projective identification. I had, of course, but couldn’t imagine how it applied here. He shared two similar experiences he’d had with equally mild-mannered teachers. Repressed rage, he told me, could induce a matching rage or extreme pain in the recipients. And it could occur not just in one person, but several.

This felt like an epiphany. I’d never thought to apply projective identification to social group interactions. It forever changed the way I view group dynamics such as teacher trainings, workshops, and even larger social happenings. And it gave me a way to recover from projective “gifts” so they wouldn’t keep on giving.

Projective Identification + Social Contagion

As it turns out, projective identification occurs frequently between social “ingroups” and the people they mark as their “outgroups,” or as “other.” In particular, dominant social groups employ it toward groups of people that they marginalize.

In modern western culture, for example, men often levy projective identification on women or those who identify as female. As it is between two people, it can become a primary way of relating. It can be a mode of learning, in which women to embody, metabolize, and transform difficult or even archetypal experiences traditionally considered “feminine,” like vulnerability or powerlessness. It can function as a way for men to rid themselves of intolerable experiences like shame or fear. And men also use it as a means of coercive control: Witness the rush of attempts to regulate women’s bodily autonomy in the U.S. and elsewhere, and the particular lack of exceptions for rape or incest. These actions are meant to “paint” our insides with fear, shame, despondency, and lack of agency.

When what the culture paints on our insides becomes nearly identical to what we digest and take on, we get internalized misogyny.

But the projective identification isn’t always one-to-one: Sometimes our own paint mixes with the culture’s painting, and the result differs from the projection. Instead of internalized misogyny, we might feel a righteous, galvanizing rage, or a paralyzing one. Or something else entirely.

And then there’s white supremacy. Many brilliant Black, Indigenous, and Writers of Color have described eloquently the way white people use projective identification to try to displace our intolerable feelings, experiences, and unprocessed trauma not onto, as in projection, but into the direct experience of BIPOC. This includes the experience of shame, fear, and rage. And the goal, however unconscious, is to protect white people (and whiteness itself) from discomfort.

Consider the way a growing number of politicians and parents don’t want their children to “feel uncomfortable” about their history or their social identity; they’re attempting to pass laws that ban books that might possibly elicit discomfort. Or prohibit the teaching of accurate history that could incur the experience of shame and remorse. Or abolish affirmative action in favor of what people in dominant culture insist is a “merit based” system. These are all actions that attempt to displace discomfort into someone else.

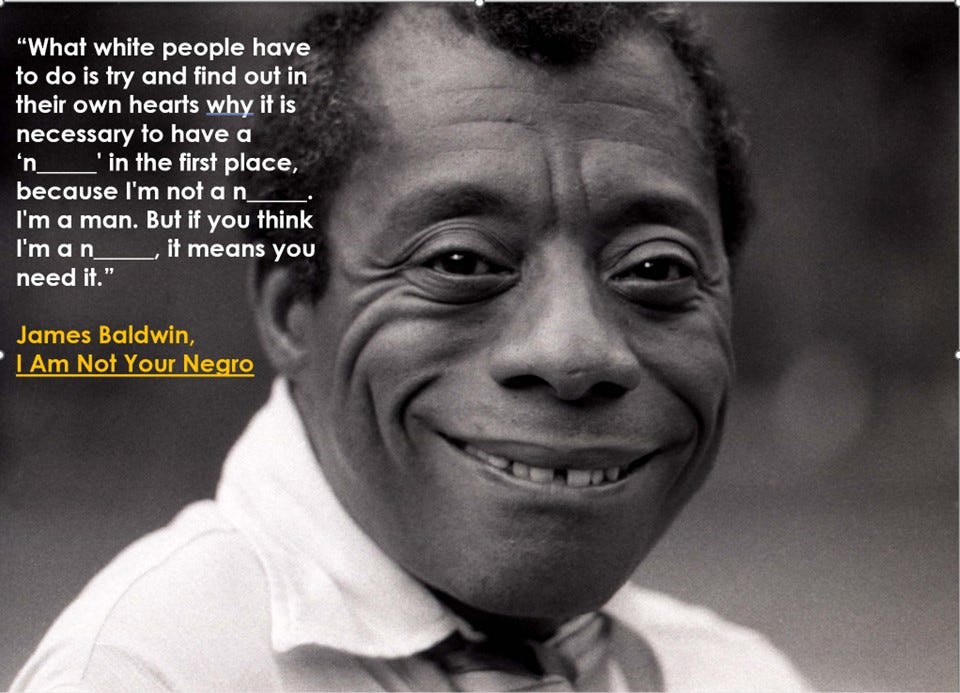

James Baldwin talked often about white people needing to take their projections back. In the spectacular film I Am Not Your Negro, for example, he said,

“What white people have to do is try and find out in their own hearts why it is necessary to have a “n_____” in the first place because I’m not a “n_____.” I’m a man. But if you think I’m a “n_____,” it means you need it.”

Here, Mr. Baldwin’s use of the term “need” highlights the intolerable, ancestral experiences of inferiority that exist in us, the lack of will to acknowledge them, and the attempt to evoke it instead in the very group we marginalize. This gets covered up by the sense of superiority, unconscious though it may be at times, that white people can cultivate.

And then there’s the brilliant Toni Morrison. In a 1993 interview, Charlie Rose asked her how she responds to everyday racist encounters. Her cut-to-the-heart bulls-eye response evokes the projective identification inherent in both overt and covert racism. Ms. Morrison says,

“Don’t you understand that the people who do this thing, who practice racism, are bereft?” said Morrison. “There is something distorted about the psyche.”

“If I take your race away, and there you are, all strung out. And all you got is your little self, and what is that? What are you without racism? Are you any good? Are you still strong? Are you still smart? Do you still like yourself? I mean, these are the questions.”

“If you can only be tall because somebody is on their knees, then you have a serious problem. And my feeling is that white people have a very, very serious problem. And they should start thinking about what they can do about it. Take me out of it.” [Emphasis mine.]

Ms. Morrison’s piercing, bad-ass response hits so many points: A distorted psyche. (The use of primitive defenses.) “And all you got is your little self.” (A clear-cut reference to the underlying inferiority.) “If you can only be tall because somebody is on their knees.” (Again, inferiority and the conditions for projective identification.)

As a reminder, projective identification doesn’t result in a one-to-one, projection-to-reception relationship. For example, inferiority can be projected, and something different can be received.

In both small interpersonal (one-to-one) and group interpersonal (group-to-group) interactions, projective identification does not force us to incubate the projective experience. In other words, we have agency.

Toni Morrison points to this agency, and to the remedy for projective identification: “Take me out of it,” she says. Which is a way of handing the projection back to its source and asking them to take it back and process it.

My Added Take: Defense mechanisms were first discussed in the 1800s by Sigmund Freud, widely considered to be the “grandfather” of psychoanalysis and modern psychiatry. Psychiatry and psychology have recently incurred criticism (and fairly so) for their colonial lens on mental health and for the racism inherent in the institutions that confer degrees, publish papers, and treat BIPOC clients. There’s also racism inherent in what “mental health” is, who gets diagnosed, and what diagnostic labels health professionals give them. (There’s a ton of research on this; it’s a topic for another column.) It seems fitting to me that the defense mechanism of projective identification initially put forth by colonial forces can turn the lens on the colonial nature of the institutions that first came up with the notion.

If we want to contribute to inclusivity and equity initiatives, or at least refrain from contributing or causing harm, one powerful starting point is learning to become more “comfortable” with our own discomfort, particularly around issues of systemic inequality. This means taking back our social projections.

Defense Against the Dark Arts

Here are a few nodes of inquiry that can help you identify when someone has employed projective identification with you—and, I hope, to help you recognize when you use it with others. (We all do it at times, even if it isn’t our primary defensive modality.)

First, it helps to name the experience you’re feeling on the inside: sensations and emotions, and their location. In naming what’s happening, you’ll find the seeds of self-determination. Spend time with the experience—really inhabit it. Try the Sensory Differentiation exercise in last week’s column (just scroll to the bottom).

Now you can get a little more general with your inquiry. What do you most often feel in response to interactions with that person? What are the sudden, invasive, and intense emotional states you feel most often? (Think worthlessness, lack of deservedness, rage, shame, or fear of abandonment.) Is it a one-to-one match? Or might the paint show up in a different pattern on your canvas?

You can also study that person’s interactions with others. What sensations, emotions, and experiences do they elicit in the people they come into contact with? How do others feel in response?

Take Out The Trash. By “trash,” I’m referring to the projections placed inside you. For this, it helps to determine what’s “in you,” and how and where it registers. But it also helps to have a “release valve” to let experiences that aren’t inherently “yours” exit your body. Connective tissue self-massage provides a great way to move more deeply to the space under your own skin, and to let projections you’ve taken in “move out.”

For additional connective tissue practices and embodied meditations that support boundaries and embodiment (plus body classes and Masterclasses), join my other email list, which is devoted exclusively to that. (When you do, you’ll also get my Survive + Thrive Guide with several practices embedded directly inside.)

Boundaries are not a mental construct; they happen through and in our bodies. These practices jump start better boundaries; when you do them regularly, you become a less “ideal” target for projective identification.

And I’ll close in the spirit of Ms. Toni Morrison. These practices help embody her words: “Take me out of it.”

Using the icons at the top and bottom of this article, you can like, subscribe, share, or restack the article. Or you can use the buttons below.

"painting your insides onto someone else's canvas" is such a powerful description - and puts just the right words around this enigmatic experience. It's tricky to tease out what is "just contagion" vs what could be projective identification...using your beautiful metaphor of painting on our inside canvases, I often realize I have a copy of someone's insides inside me... but it's hard to know if that person put it there (a violation?), I picked up myself (perhaps a subconscious choice) or it just kinda got replicated from two bodies/energies being in contact (humanity happening). I just loved the artful language in this article and esp the practices for protecting against performing or receiving these "dark arts" <3