Interventions for Better Sleep, Body Rhythms, & Well-Being

Sleep and circadian rhythms are intertwined. Any time we talk about sleep disturbance, circadian misalignment is involved, and vice versa. And when we explore how to build better sleep, we also mean tuning into our rhythms better. This reciprocity has huge implications for our health.

Interoception—the ability to receive, appraise, respond to, and regulate signals that come from the body—is also involved with sleep and circadian rhythms. Many of the mechanisms involved in better sleep and body rhythms are related to interoception.

And the conscious development of interoceptive awareness helps us pick up on the body’s signals. These signals include the quality of our sleep, levels of stress, impact of sleep loss or good sleep, alignment of our circadian rhythms, and how these factors affect the mind, brain, and body. This awareness gives us critical feedback in making beneficial adjustments. Because interoception also relates to circadian rhythms, my take of the research is that there’s an optimal period of time during the day to employ interoception, and a time to put it “to rest.”

All this means that the tools we use to potentiate sleep, the timing of when we use them, and the awareness of their effects are vital to our health and well-being.

The tools can include the timing of light viewing, eating, exercise, vitamins, screen time, contemplative practice, and more. (You can check out my online Masterclass on better sleep for more information.)

One theme: Many tools, interoception included, are two-way streets: They affect sleep and our circadian rhythms, which affect them in return. And the tools aren’t “outside us” and don’t need to be purchased or wielded on the body. They’re already happening within us, and the therapeutic nature of the tool is in the timing of how we modulate them.

If you’re lucky enough not to change your clocks twice a year, the therapeutic interventions referenced here still apply to you. For convenience, I’ve lined out what to try if you’re moving the clocks forward, backward, or not at all.

Before we begin, a quick review of circadian rhythms and chronobiology. (For more on those, you can take my online Masterclass on circadian rhythms, sleep, jet lag, and social context.) In my last column, I explored chronobiology, defined in this way:

The field of chronobiology focuses on the biological and cyclical rhythms in the body and, I’d add, the body’s relationship with time itself. Almost all species have internal rhythms and a sense of time. We have internal circadian (approximately 24-hour) clocks that generate and shape daily cycles in our physiology, emotion, and behavior.

The term “circadian” comes from the word circa, meaning approximate and diem, meaning day--so, “approximate day.” Our 24-hour circadian rhythms are generated by a molecular circadian clock which is present in nearly every cell in the mammalian body.

Without contextual information from the outer world, you have a daily rhythm closer to 24.2 hours. Getting sunlight adjusts your behavior to a solar day; otherwise, your rhythm would be way off. In just five days without any sunlight, you’d be off by a full hour. In one month, you’d be off by a full six hours. So tuning your body clocks is essential to well-being.

This could be several months’ worth of columns! To make it digestible (see what I did there?) I’m going to focus on three areas for well-being that I adjusted recently in the context of the recent bump forward of the clocks in many parts of the U.S. I found this highly effective for me, and wanted to share them with you. These are: the gut microbiome, light exposure, and eustress, the kind of stress that enhances well-being. And I’ll touch on interoception.

For background, I have IBS and am an empath, and find that my gut is my “first responder” to literally everything. So that’s always a focal point for me; it may not be for you.

The Gut Microbiome, Digestion, and Circadian Rhythms

What does the gut have to do with circadian rhythms and sleep, you might wonder?

It turns out that circadian rhythms regulate much of gastrointestinal function, including:

the microbiome and its balance

cell growth

gastrointestinal motility

intestinal permeability

intestinal mucosa and immunology

digestion

nutrient assimilation

electrolyte balance

With respect to the above areas of functioning, the GI tract behaves differently during the day when we consume food than it does during the night when we sleep.

Disruption of circadian rhythms, like the kind daylight savings time elicits, has negative consequences for all these areas of gut function. In fact, circadian disruption underlies a range of gastrointestinal diseases.

One of the strongest influences on circadian rhythms in the intestine is the timing of food consumption, which is a strong enough influence to override the body’s master clock.

Genetic variations in the molecular circadian clock correlate with poor gastric motility in humans. Researchers think that disruption of circadian rhythms compromises gastrointestinal motility, the contractions that help move food through the GI tract—and therefore, play a role in GI disorders involving dysmotility, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), functional dyspepsia, GI symptoms in diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease.

In addition, disruption in our circadian rhythm can have a negative impact on intestinal barrier function. Researchers have found that in mice, disruption of rhythms such as light-dark shifting impairs intestinal barrier integrity. (This is often referred to as leaky gut syndrome by functional medicine specialists and researchers. Despite the research support, the existence of leaky gut is still disputed by mainstream medicine practitioners.) Why does this matter? The intestinal barrier prevents dietary antigens and inflammatory molecules from permeating the intestinal mucosa and promoting or worsening inflammation-mediated diseases. (One inflammatory disease intimately linked with the gut is depression.)

Studies also demonstrate that circadian disruptions alter the gut microbiome, resulting in an abundance of pro-inflammatory (“bad”) microbes and a decrease in anti-inflammatory (“beneficial”) microbes. (The “bad-beneficial” label is a false binary, as even “bad” microbes do “beneficial” things like eat brain plaque.)

This emerging research meshes with what science already knows about the gut is rooted in the insight that one of the strongest influences on circadian rhythms in the intestine is the timing of food consumption, and that this influence can override even the master clock.

We don’t just eat something, and then our enteric nervous system jumps into action to digest it. Our gut prepares for eating in advance, by secreting gastric juices and digestive enzymes. And it does this based on a kind of cellular memory of the rhythm of when we usually eat (This is one reason why regular mealtimes help the gut microbiome, which makes it a therapeutic tool you can employ year-round).

The Gut Intervention

One reason why travel and daylight saving time (and the return to daylight standard time) mess with digestion is that the cues for when to eat change, preventing us from eating on our normal schedule. This can lead to impaired intestinal motility and digestive issues.

This year, on DST, I decided to take circadian rhythms into account in deciding when to eat. But I did something different than asking my body to adjust all at once to moving my mealtimes forward.

To make this simpler, I’m going to use the term body time to indicate when my body is used to eating, and clock time to refer to the newly adjusted chronological (clock) time.

I usually eat my first meal of the day at 10:00 a.m. I knew that my gut would be preparing in advance, perhaps around 9:30 body time, for breakfast. I’m in the Northern Hemisphere, and we moved the clocks forward: If I ate at 10:00 a.m. clock time, it would really be 9:00 a.m. body time, well before my body prepared for the meal. This could cause issues that might snowball for the rest of the day. In fact, it wouldn’t really be 10:00 a.m. body time until the clock showed 11:00 a.m. clock time. Therefore, I had my first meal at 11:00 a.m.

You might expect me to do the same thing in the evening, eating also on body time. But I didn’t, and here’s why.

Normally, I try to finish my first meal by 7:00 p.m. and go to bed around 9:45 p.m. But this brings up another issue relating to food timing and sleep timing and how they intersect. Because I have gut issues, paying close attention to this felt super important to me. (If you don’t have any gut issues, you might choose another lever for better sleep.) Eating causes a moderate rise in body temperature and inflammation levels; having extra time between my final meal and bedtime allows my body temperature and digestion to percolate, and inflammation to go down a little, before I sleep.

When the clocks move forward, it asks us to go to bed earlier with respect to body time, which is a challenge. It’s much easier to push our bodies to stay up a little later than it is to prepare them to go to bed earlier, when we’re not as tired and the outside cues like light and screens and social activity tell us it’s still early.

Knowing this, I decided to have my evening meal well before bed, at 5:30 p.m. body time and 6:30 clock time, which was one hour earlier than usual. I knew my digestive system would be less prepared to eat then, and added more fermented foods to the beginning of my evening meal to support my gut microbiome. Eating earlier also gave my body more time to digest before sleep, and less chance of indigestion and inflammation (which also dovetails with nervous system arousal) before sleep. This worked well; surprisingly, it also helped me feel tired enough to go to sleep an hour earlier body time.

This brings me to the final point: Regular eating, fermented foods, and leaving time between eating the final meal and going to sleep are therapeutic tools I use regularly, not just when changing the clocks or traveling, but because of the intimate connection between the gut, immunity, and mood. So it’s a lever you can use all year round.

If you’d like to try what I did, here’s what I’d recommend:

If going into Daylight Savings Time (clocks go forward): Have your first meal of the day at the regular time on body time, which would be an hour later on clock time. And You can also try having your last meal one hour earlier body time, which is the regular time on clock time. I did this for three days to ensure that I adapted.

If going back into standard time (clocks go back): Here, you can do the opposite: You can have your first meal of the day at the regular time on body time, which is an hour earlier on clock time. (In the fall, when we return to standard time, I’ll have my first meal at 10:00 a.m. body time and 9:00 a.m. clock time.) And if you have GI issues, finish your last meal three hours before you go to bed.

If you’re lucky enough to be on standard time all the time: You can continue to observe eating as close to the same time every day as you can. To help you sleep better, have your last meal 2.5 to 3 hours before going to sleep.

If you’d like to learn more about your gut and the enteric nervous system or belly brain, I’m offering a 2-hour Masterclass in April to cover emerging research on the enteric nervous system and its implications for mood, immunity, and well-being. (I offered a Masterclass on this back in 2020, and exciting new work has happened in the fields since then that feels important to convey.)

Building In Good Stress

Most of us grew up with the notion that stress is bad for us, and endangers our health. Yet without stress, our nervous system can’t thrive and sometimes, even survive. In order to learn new things, a phenomenon known as neuroplasticity, our nervous systems need change and small to moderate amounts of stress. In fact, stress (including spikes in cortisol) can help our brains and bodies integrate new learning. What makes this complicated is that whether or not stress turns out to be beneficial also has to do with the type, duration, and intensity of the stressor.

My take: It also has to do with the timing of the stress.

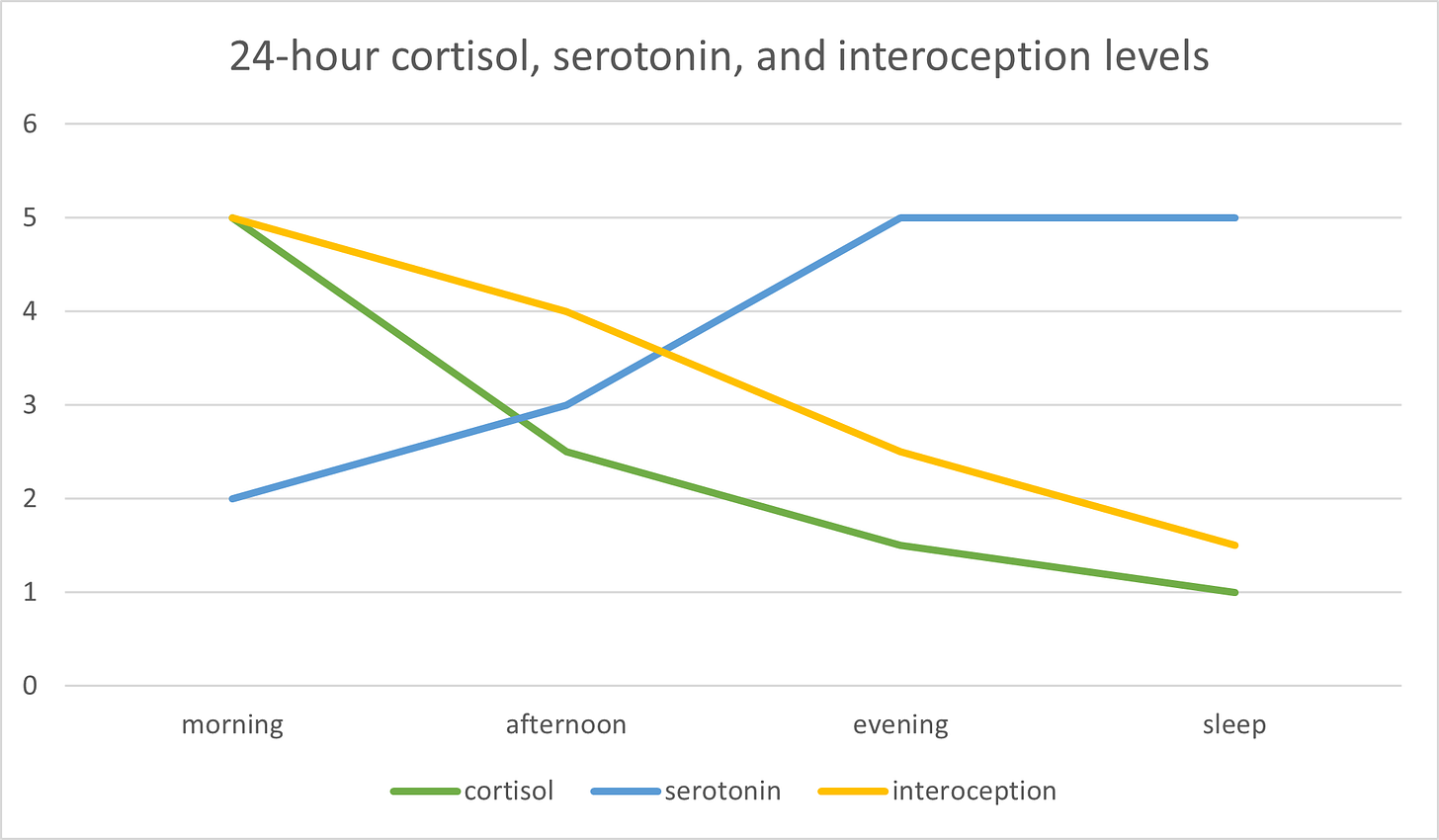

Ideally, cortisol levels follow a 24-hour (circadian) rhythm. They peak in the morning around 6:30 a.m. along with a rise in blood pressure. Cortisol has a decline throughout the day, and reaches its lowest levels around midnight.

People with anxiety, insomnia, and a history of trauma or posttraumatic stress disorder often have an almost reverse rhythm: Their cortisol levels don’t peak in the morning, when the peak helps jump-start the day. Instead, they rise in the evening, when it’s time to sleep. This can raise body temperature. Unsurprisingly, people with anxiety and insomnia often have cortisol peaks and a higher basal body temperature at night, which makes sleep difficult.

As a survivor of assault, I notice that despite my devotion to daily contemplative practice, body movement, and restorative yoga, I frequently experience a subtle level of activation and vigilance at night. (The same can happen for people who go through childhood trauma or who have higher nervous system set-points—that is to say, tip easily into hyper-arousal.) Travel, extra stress, circadian disruption, and even digestive issues can trigger these watchful periods. I’ve come to see these periods less as “enemies” of my well-being, and more as good signs of vulnerability and humanity.

I’ve been fascinated in recent years by the notion of eustress, the kind of stress that’s good for you and how to build it into your life.

For the past year, I’ve been playing with building in small amounts of eustress through cold exposure, particularly through cold water immersion therapy. I’ve made it through my first winter cold dipping, and am super excited about its impact on my interoception, inflammation, and sense of agency. I’ve written about this on Instagram, and will do a column on it at some point.

If you’d like to play with your cortisol rhythms and to try cold immersion, I highly recommend starting with 20 seconds of cold water at the end of your shower or bath. If you increase the time, consider doing so slowly, and observing how your body reacts. It took me a few months to increase to 30 seconds; if I did so too early, my body had a hard time re-warming.

A key point: I do this in the morning so the cortisol spike happens early. This really helps decrease any evening cortisol spikes I have. And when I do this outside, it also allows me to engage in my daily light-viewing practice at the same time.

If going into Daylight Savings Time: Cold immersion therapy at sunrise, and then a brief walk

If going back into standard time (clocks go back): The same

If you’re lucky enough to be on standard time all the time: Same same!

Caffeine Intake.

If you’ve ever attended an on-the-road workshop or teacher training with me, you’ve likely seen me with a huge, brightly-colored thermos filled with a caffeinated latte. I found this helpful for jet lag, particularly when traveling overseas.

For the past year, though, I’ve stopped that completely. I use coffee medicinally (for the antioxidants and cortisol spike) only in the morning.

Caffeine, however, interferes with our adenosine receptors that help build the pressure to go to sleep. For this reason, and on the recommendation of sleep expert Matt Walker, author of Why We Sleep, I wait two hours after awakening before having any caffeine to “clear” the interference and allow sleep pressure to build. Light-viewing and my morning walk (done at the same time) also help clear the adenosine receptors. I have less than a cup of coffee, and always before 9:30 a.m. in order to tone down any nervous system hyper-arousal and build sleep pressure.

For Daylight Saving Time (clocks moving forward), I knew that I’d need to go to sleep an hour earlier. So I stopped all caffeine intake starting a few days before and going a few days afterward. This also really helped me be ready to sleep earlier.

When going back into standard time, we need to stay up later. I’m not sure how I’ll use this lever in the fall, but will post again then. Technically, I could continue caffeine in the fall in order to stay up later in the evening. However, the derangement of the time change in general makes me think that my nervous system is responding to the circadian disruption itself as a stressor, and as a cue to become more vigilant. (In last week’s column, I referenced mood changes that occur following the daylight saving change.)

If going into Daylight Savings Time: Consider avoiding caffeine for a period anywhere from a week prior to a week afterward. Notice the changes in your sleep patterns, which will give you valuable information about how your nervous system responds to these artificial time changes.

If going back into standard time (clocks go back): The same, or consider caffeine abstinence if your nervous system is stressed by this change. (Despite the media story about “getting an hour extra of sleep,” this doesn’t happen (because circadian misalignment!) and this change, too, is tough on our nervous systems.

If you’re lucky enough to be on standard time all the time: Do your thing! Consider re-evaluating your caffeine intake in relation to nervous system arousal and sleep.

Interoception

This might not be an intuitive connection, but interoception is related to circadian rhythms and therefore, to sleep. Many of the factors relating to sleep discussed above (gut functions, cortisol, blood pressure, body temperature, and stress) are part of interoception. That means they’re happening all the time.

In addition, levels of conscious interoception, which you can think of as interoceptive awareness, also affect sleep and circadian rhythms and are affected by them in return. Sleep and sensory processes have a dynamic, complex, and reciprocal relationship within each modality of interoception, including thermoception (temperature sensing), nociception (pain sensing), visceral sensations (enteric nervous system), and subjective feelings about these sensations.

Previous columns explored the relationship between low levels (and accuracy) of interoception and depression. But it turns out that both anxiety and hypermobility are related to high levels of interoception and to the tendency to focus intently on, catastrophize, and have a nervous system alarm response, to body sensations.

During sleep, we experience a suppression of interoception in areas of “behavioral defense responses,” such as hypoxia, coughing, shivering, and withdrawal reflexes. This lowering of interoception prevents arousals + protects sleep. But input from pain, breathing, and heartbeats can generate cognitive evaluation just as we’re trying to fall asleep; this contributes to insomnia.

My take: PTSD can create a higher baseline arousal level, and therefore greater involvement of interoception, which doesn’t decrease as it should before sleep.

In one study of 64 participants aged 21-70, people with insomnia had higher amplitudes of heartbeat evoked potentials (HEP), a measure of interoception. During the eyes-closed state called “pre-sleep” that occurs prior to falling asleep, their brains activated in response to their own heartbeats. The “appraise” or “interpret” part of the ability to receive, appraise, respond to, and regulate body sensations goes awry, and the brain doesn’t adapt to ever-present heartbeats.

At the same time (because these elements aren’t binaries and therefore aren’t mutually exclusive), low levels of interoceptive accuracy are linked to poor sleep quality.

My take: I suspect that in time, scientists will map interoception across the 24-hour circadian cycle, and find that it naturally peaks in the first eight hours of the day, begins to decrease in the second eight hours, and as we now know, reaches its quietest point as we fall asleep. For this reason, I recommend “stacking” interoception most strongly in the first eight hours of the day, using bodyscans and other interoceptive tools in the first part of the afternoon or second eight-hour period, and then briefer check-ins in the final part of the day.

When I do my pre-sleep routine, which consists of connective tissue self-massage, moxa (an Asian acupuncture tool), and journaling, I let myself sink into the activities and feel myself doing it. I do a brief gut check-in for reasons I’ve already shared, and to take herbs if my gut happens to be struggling. But I don’t deliberately cultivate interoceptive awareness during pre-sleep. This has helped me relax into sleep more easily.

I made you a quick chart to show how cortisol, serotonin, and interoception levels might ideally fluctuate, and how working with their natural rhythms can help your sleep. (Ideally the graph would be rounded, but I couldn’t get that to work.)

If this kind of “therapeutic tools” column is helpful to you, feel free to like, comment, forward to someone who might benefit, or become a supporter. (Comments are open for paid subscribers only.)

There’s much more to be said on tools for better sleep, which I create Masterclasses and numerous Instagram and Facebook posts on.

Sleep, Circadian Rhythms, and Social Context

There’s much to say on the social context of these tools. Light viewing, in particular, is more challenging for people who start work early in the morning, and changing mealtimes can be difficult for parents of young children. For more on sleep tools and social context, view this 9-frame post on Instagram.

One final thought that feels important to me: These “therapeutic interventions” posts aren’t about the “biohacking” or “optimization” themes that abound right now in the area of wellness. These posts hew to the spirit of cultivating greater relationality with the body, including its rhythms, and with nature rather than improved performance or productivity. For this reason, therapeutic interventions are a way of building our self-to-body relationship and in many ways, allowing our conscious minds (the self) more vulnerability and humility in this relationship.

Using these tools over the past ten days, I noticed that I was “off,” which resulted in some proprioceptive challenges and on a couple of nights, weird digestive and immune things. This felt comforting. It reminded me of one of embodiment’s greatest lessons: It’s not about mastery, but about relationship.

Sources:

Circadian disruption underlies a range of gastrointestinal diseases: Voigt, R. M., Forsyth, C. B., & Keshavarzian, A. (2019). Circadian rhythms: a regulator of gastrointestinal health and dysfunction. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology, 13(5), 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/17474124.2019.1595588

One of the strongest influences on circadian rhythms in the intestine is the timing of food consumption: Konturek, P. C., Brzozowski, T., & Konturek, S. J. (2011). Gut clock: implication of circadian rhythms in the gastrointestinal tract. Journal of physiology and pharmacology : an official journal of the Polish Physiological Society, 62(2), 139–150.

the GI tract behaves differently during the day: Hoogerwerf W. A. (2009). Role of biological rhythms in gastrointestinal health and disease. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders, 10(4), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-009-9119-3

Researchers think that disruption of circadian rhythms compromises gastrointestinal motility: Yamaguchi, M., Kotani, K., Tsuzaki, K., Takagi, A., Motokubota, N., Komai, N., Sakane, N., Moritani, T., & Nagai, N. (2015). Circadian rhythm genes CLOCK and PER3 polymorphisms and morning gastric motility in humans. PloS one, 10(3), e0120009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120009

disruption in our circadian rhythm can have a negative impact on intestinal barrier function: Summa, K. C., Voigt, R. M., Forsyth, C. B., Shaikh, M., Cavanaugh, K., Tang, Y., Vitaterna, M. H., Song, S., Turek, F. W., & Keshavarzian, A. (2013). Disruption of the Circadian Clock in Mice Increases Intestinal Permeability and Promotes Alcohol-Induced Hepatic Pathology and Inflammation. PloS one, 8(6), e67102. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067102

Studies also demonstrate that circadian disruptions alter the gut microbiome: Voigt, R. M., Forsyth, C. B., Green, S. J., Mutlu, E., Engen, P., Vitaterna, M. H., Turek, F. W., & Keshavarzian, A. (2014). Circadian disorganization alters intestinal microbiota. PloS one, 9(5), e97500. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097500. See also: Voigt, R. M., Summa, K. C., Forsyth, C. B., Green, S. J., Engen, P., Naqib, A., Vitaterna, M. H., Turek, F. W., & Keshavarzian, A. (2016). The Circadian Clock Mutation Promotes Intestinal Dysbiosis. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research, 40(2), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12943

Sleep and sensory processes have a dynamic, complex, and reciprocal relationship: Wei, Y., & Van Someren, E. J. W. (2020). Interoception relates to sleep and sleep disorders. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 33, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.11.008

In one study of 64 participants aged 21-70: Wei, Y., Ramautar, J. R., Colombo, M. A., Stoffers, D., Gómez-Herrero, G., van der Meijden, W. P., Te Lindert, B. H., van der Werf, Y. D., & Van Someren, E. J. (2016). I Keep a Close Watch on This Heart of Mine: Increased Interoception in Insomnia. Sleep, 39(12), 2113–2124. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.6308

low levels of interoceptive accuracy are linked to poor sleep quality: Ewing, D. L., Manassei, M., Gould van Praag, C., Philippides, A. O., Critchley, H. D., & Garfinkel, S. N. (2017). Sleep and the heart: Interoceptive differences linked to poor experiential sleep quality in anxiety and depression. Biological psychology, 127, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.05.011