The other day I ran into my neighborhood friend Jaden and his pit bull Sampson at the park near my house. I hadn’t seen then in many months. Even from a distance, I could tell that something about Jaden’s body was radically different. Up close, the poetics of his movements struck me immediately: the fluid, graceful gestures he made with his hands, and the way his body seemed almost to dance through the air. Even Sampson seemed different, straining his leash in a more abundant way. “You’re moving so differently!” I enthused. “Did something happen in your body?”

Surprised that I’d noticed, Jaden shared that he’d been in chronic pain for several years. In fact, it turned out that I’d only ever seen him move in the context of pain. Halfway through the third year of the pandemic, he underwent hip replacement surgery, followed by a long and arduous rehabilitation. Now his long and arduous journey was coming to a close.

But it wasn’t simply the absence of pain that spoke volumes. The revelation unfolding before my eyes had to do with the way Jaden moved his body through space, and how he occupied and interacted with the built space of the park around him. It also encompassed the way, as a professional musician, he moved his body in tempo with his words. Jaden had even noticed a softening in the way he felt about and related to his body.

Hip surgery and relief from pain aside, what exactly was at play here? The changes in Jaden’s movement patterns, the way he navigated space, and even the emotional tone with which he did so, are key elements of proprioception, sometimes referred to as our sixth sense. From the Latin roots proprius, meaning “of one’s own,” and capere, “to take or grasp,” proprioception is one of the central ways through which we grasp, or know, ourselves.

Especially in the yoga or fitness worlds, people often describe proprioception as “body awareness” or equate it with movement or exercise. This is particularly true of advanced asana or fitness routines, as though the more advanced our movement, the more advanced our sense of proprioception.

In one small respect, this notion has some truth to it. Proprioception is connected with movement. And it’s linked to body awareness, too. But there’s so much more to proprioception—and how to keep this sense fresh and alive—than movement or basic body awareness.

Proprioception is more of a system than it is a sense. It encompasses several “mini” senses: our awareness of movement, the position of our body and its parts in space, and how we occupy space. It also involves our sense of balance, of effort and force and heaviness, and our posture or shape. Proprioception also includes the way we monitor and regulate the space around our bodies—and sometimes others’ bodies too.

Proprioception also includes peripersonal space, the boundaries between ourselves and others, and also in homes and communities and even countries. And as you might be intuiting, it also includes the way our built spaces relate to environmental and cultural factors.

Proprioception involves a symphony of actions, reactions, predictions, and functions in which multiple instruments play in concert, at times harmonizing and at times in a state of intelligent entropy.

Although this is all part of proprioception, the fields of yoga and fitness often leave this out of our practice or workout. Integrating this information can make these fields more culturally competent, more socially integrative, and ultimately, more therapeutic.

Proprioception Then and Now

Proprioception has been a focus of research since the 1800s. Perhaps out of necessity, the field divides the study of proprioception into its separate aspects. This ranges from scientists who study the most quantum level of proprioception like genes, ions, or cells, to receptor and muscle fibers, to the space that surrounds our bodies. While doing research for my book, I’ve noticed that like many other areas of scientific study, there’s a scarcity of dialogue between sub-fields or with “outside” fields that relate to proprioception, like movement rehabilitation, cultural studies, or architecture.

Two years ago, I interviewed a senior researcher (think over 250 publications) about the muscular level of proprioception. At his request, I’d submitted questions in advance, including one that touched on the relationship between fascia and proprioception. “It’s just ridiculous,” he spat out in answer, “that those fascia people seem to think that what’s happening at the level of my right ear affects what’s happening way down at my foot!” He couldn’t believe the naivete of the concept of body sheaths, while I found it hard to imagine not believing it. Needless to say, these fields need more crosstalk than they’re getting.

A quick word about fascia and the body’s inner senses, which I’ll touch on in later columns: According to Robert Schleip, our richest (and largest!) sensory organ is not our eyes, ears, nose, or balance system, but our muscle and fascia. Fascia is alive and intelligent, innervated by a dense network of mechanoreceptors. These include interstitial mechanoreceptors (part of the proprioceptive system I mention below), smooth muscle cells in fascia which regulate fascia tension. Stimulating these interstitial cells alters proprioceptive input to the central nervous system. It can trigger a change heart rate, blood pressure, rate of respiration, and overall vagal tone.

The term “tensegrity,” or tensional integrity, which is part of the fascial lexicon, also shows up over and over again in proprioception research. Tensegrity hints at a gravitational force which keeps our bodies engaged. Despite the skepticism of the noted researcher I interviewed, fascia forms a true continuity throughout the body. Its fluid dynamics are also central to the brain, which is a liquid system. It’s also directly related to interoception.

For more about the fascial system and it’s connections to proprioception, interoception, and nervous system functioning, check out our Masterclass Getting Under Our Own Skin: Fascia, Interoception, and Emotional Health.

The Nuts + Bolts

Proprioception doesn’t have a central organ in the way that, say, our sense of smell has the nose. It extends like a web (more allusions to fascia!) throughout the brain, body, and even the mind.

Like interoception, proprioception has a system of peripheral receptors located in tissue in our muscles, tendons, fascia, joint capsules, ligaments, and around our joints.

The simplest movements, particularly rhythmic behaviors like walking, running, swimming, breathing, and chewing, don’t take much conscious effort for most of us. These movements are orchestrated by groups of cells that reside between the lower thoracic and lumbar regions of the spinal cord. Called central pattern generators, these neural networks can generate organized movement patterns independent of sensory input or direction from the brain. They allow our limbs to alternate between left and right and between flexion and extension.

Coordinated movements and skilled motor tasks require more extensive and detailed communication between the body and the brain. This happens thanks to a diverse array of sensory neurons which gather feedback about your body’s location and movement. Your eyes and ears house some of these cellular receptors; your muscles, tendons, skin, joints, and connective tissue accommodate others.

Many of these, called proprioceptors, sense and communicate continuous, fine-grained detail about the position of your limbs and other body parts in space. These receptors offer inputs that assess and communicate the degree of muscle length, changes in muscle length and tension, joint angles, and skin stretch. The most important are muscle spindles, stretch detectors embedded in your muscles which listen for and respond to how much and how fast your muscles lengthen or contract. Muscle spindles report on the angle of your joints and the stretch of your skin. They also forecast the result of your movement. When you’re swimming and lift your left arm out of the water to take a new stroke, for instance, the muscle spindles signal your arm’s movement as well as its future position in space.

Skin receptors support discriminative touch, the kind that happens when a hot mug touches your forearm. They also use tactile feedback to provide information about the skin’s deformation—like the stretch of your skin that happens as you take another crawl stroke—during movement and contact with objects.

Joint receptors detect the limits, or extreme angles, of joint rotation. (Think of the signal that tells you that your hips can’t or shouldn’t move deeper into a yoga pose.) The majority of joint receptors actually do not convey joint position sense. They only respond at the limits, or extreme angles, of joint rotation and are considered limit detectors. (This relates partly to why people with hypermobility can transgress the limits of their joints easily when stretching in a yoga practice—more about that in a moment.)

Your proprioceptors gather sensory information and send it to the brain and spinal cord (your central nervous system). Nerve impulses carrying somatic sensations travel along fibers to the cell bodies of their respective neurons, which are located near the spinal cord. There, the release of neurotransmitters passes the signal along to fibers of the spinal cord itself, which run up to the brain.

Another potential route for ascending proprioceptive feedback is the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway, hypothesized to be a pathway for consciously accessible proprioceptive information.[v] There’s much more to what happens once information gets to the brain, which I’ll discuss in future columns.

Proprioception + Emotional Health

Proprioception typically happens below the surface of our awareness. For that reason, we don’t think about it much. We’re more likely to become conscious of it when trying new movements, which is one reason why I’m so dedicated to novel movement (the kind we’re not used to doing) as a form of proprioceptive and emotional therapy.

We often generate more awareness of proprioception when something interferes with it. For example, we often experience proprioceptive loss after an illness or surgery: a kind of “forgetting” of movement. And we experience it as an accompaniment to aging; this isn’t just due to sarcopenia, a loss of muscle mass, muscle strength, and performance that begins in mid-adulthood and accelerates over time. It also happens because of a disruption in the body-to-brain connection—that is to say, in the fluency with which the body and brain communicate. This dysfluency occurs as we age, not only in proprioception but in other inner senses like interoception and body agency.

Proprioceptive loss is an emblem of neurodegenerative and neuromuscular diseases like Parkinsons, ataxias, and other illnesses. Neuromuscular disorders often affect muscle spindle function, which contributes to unstable gait, frequent falls, and balance problems. But these disorders have a huge impact on emotional and social functioning.

My take: I’ve worked with people who have Parkinson’s, ataxias, and other neuromuscular issues for decades. Many also struggle with profound depression, social withdrawal, and a decrease of interpersonal skills. These issues have historically been described as occurring as a result of Parkinson’s, or alongside it. I’m convinced, however, that the loss of movement itself is a causal factor in the depression and related social-emotional skills—and that restoration of movement can have a profound influence not only on neuromuscular function but emotional well-being too.

I believe that proprioceptive loss is not a side effect of the depression in these disorders, but a major driver of it.

Social Proprioception and Body Justice

Dominant culture muscles in on every facet of proprioception. There’s so much to say on this topic; I’ll mention several issues briefly here and touch on them in greater depth in the future.

This includes how we move and the awareness of how we move, our spatial location (where we’re welcomed and where we are ushered out of a place), our posture and movements (how we rearrange our body to protect it), how we take up space and who gets to take up space, who is centered in spaces, whether or not (usually not) we make public spaces accessible, what kinds of bodies we value, and other aspects of social proprioception.

We live in a time when body rights are challenged all over the world, including in democratic countries worldwide. Some of those body rights pertain to the ability to move, unfettered, through space.

One of the countless heinous aspects of American racism is sundown towns, all-white communities that excluded Black, Indigenous, and People of Color through laws, harassment, threats, and acts of violence. Sundown towns became prevalent in the U.S. following the end of formal enslavement and continued well into the 1900s. Following the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many sundown towns discontinued these practices, but some still maintain them in multiple forms.

This attack by social forces on proprioception makes its way into architecture and is reflected in architectural racism: Communities are designed in such a way that nuclear and hazardous waste plants are built near Black, Brown, Indigenous (BIPOC) and poor communities. Many of these communities are built close together. (This impacted the ability to socially distance during Covid.) They are built without trees, and are therefore hotter in the summer. And redlining, which restricts the purchase of home in marginalized communities and makes food sovereignty more difficult.

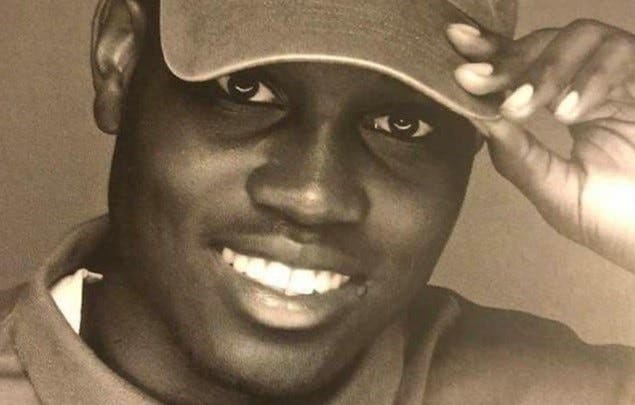

There’s so much else to talk about here. But I’d like to end this week’s column by remembering Ahmaud Arbery, and pointing to the way patriarchy and white supremacy attack the sense of proprioception directly.

On February 23, 2020, Travis McMichael, Gregory McMichael, and William Bryan chased, kidnapped, and murdered Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old Black man out for a run in a South Georgia neighborhood. In 2022, they were convicted of murder and federal hate crimes, and sentenced to life in prison; they filed an appeal in March of 2023.

To get an intimate feel for the multiple ways that racism (and patriarchy) impacts proprioception in marginalized bodies and, in contrast, privileges it in white, usually male, bodies, I’d like to quote an incredible article: Mitchell Jackson's Pulitzer Prize-winning story "Twelve Minutes and a Life" on the life (and murder) of Ahmaud Arbery. This stunning story drives home the links between white supremacy, racialization of bodies, and how outside forces shape proprioception.

As this week’s practice, see if you can note, while reading through the article, all the ways (not limited just to running) that proprioception and its constriction shows up. I’ll start with this quote, bolding and italicizing several of the many references to the way white supremacy attacks proprioception directly.

“Matter of truth, around the time Bowerman visited New Zealand and published a bestselling book, millions of Blacks were living in the Jim Crow South; by 1968, Blacks diaspora-wide had mourned the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. And by the late ’60s and beyond, the Blacks of the Great Migration were redlined into ever more depressed sections of northern and western cities, areas where the streets were less and less safe to walk, much less run. Forces aplenty discouraged Blacks from reaping the manifold benefits of jogging. And though the demographics of runners have become more diverse over the last 50 years, jogging, by and large, remains a sport and pastime pitched to privileged whites.

Peoples, I invite you to ask yourself, just what is a runner’s world? Ask yourself who deserves to run? Who has the right? Ask who’s a runner? What’s their so-called race? Their gender? Their class? Ask yourself where do they live, where do they run? Where can’t they live and run? Ask what are the sanctions for asserting their right to live and run—shit—to exist in the world. Ask why? Ask why? Ask why?

Ahmaud Arbery, by all accounts, loved to run but didn’t call himself a runner. That is a shortcoming of the culture of running. That Maud’s jogging made him the target of hegemonic white forces is a certain failure of America. Check the books—slave passes, vagrancy laws, Harvard’s Skip Gates arrested outside his own crib—Blacks ain’t never owned the same freedom of movement as whites.”

Recommended:

The Pod Save the People episode that discusses architectural racism

The MOMA explores architectural racism

Episode 1 of the All My Relations podcast series on Mauna Loa (and land as place, and how settler colonialism impacts space, place, bodies, and natural bodies)

See this article in the New York Times

Sources:

Called central pattern generators, these neural networks can generate: Guertin, P. A. (2013). Central pattern generator for locomotion: anatomical, physiological, and pathophysiological considerations. Frontiers in neurology, 3, 183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2012.00183. See also: Shadrach, J. L., Gomez-Frittelli, J., & Kaltschmidt, J. A. (2021). Proprioception revisited: Where do we stand? Current Opinion in Physiology, 21, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cophys.2021.02.003

Many of these, called proprioceptors, sense and communicate continuous, fine-grained detail: Shadrach, J. L., Gomez-Frittelli, J., & Kaltschmidt, J. A. (2021). Proprioception revisited: Where do we stand? Current Opinion in Physiology, 21, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cophys.2021.02.003

The most important proprioceptors are muscle spindles: Proske, U., & Gandevia, S. C. (2012). The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiological reviews, 92(4), 1651–1697. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00048.2011

Muscle spindles report on the angle of your joints and the stretch of your skin: Macefield, V. G. (2021). The roles of mechanoreceptors in muscle and skin in human proprioception. Current Opinion in Physiology, 21, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cophys.2021.03.003

Another potential route for ascending proprioceptive feedback is the dorsal column-medial lemniscus pathway: Tuthill, J. C., & Azim, E. (2018). Proprioception. Current biology : CB, 28(5), R194–R203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.064.

This is due in part to the incidence of sarcopenia: Cruz-Jentoft, A. J., & Sayer, A. A. (2019). Sarcopenia. Lancet (London, England), 393(10191), 2636–2646. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31138-9. See also: Palmio, J., & Udd, B. (2014). Borderlines between Sarcopenia and Mild Late-Onset Muscle Disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 6, 267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00267

Many neuromuscular diseases affect muscle spindle function, which contributes to unstable gait: Kröger, S., & Watkins, B. (2021). Muscle spindle function in healthy and diseased muscle. Skeletal Muscle, 11(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13395-020-00258-x

Sundown towns became prevalent in the U.S. following the end of formal enslavement: Read Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism, by James W. Loewen.

Following the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many sundown towns discontinued: Listen to this episode on a sundown town in Minden, Nevada on Heather McGhee’s The Sum of Us podcast

.